Pandemic - spare a thought for those who went before.

A new disease is sweeping through continental Europe at alarming speed, felling all in its path. It enters England through the south coast ports and soon reaches London where rich and poor alike succumb. Soon its tendrils spread through the whole country: even as far as Devon where the graveyards fill rapidly. It’s an all too familiar scenario. But the year is 1557 and Mary Tudor sits on the throne of England.

This was no swift killer like the sweating sickness or the plague, which, it was said, could see a man merry at daybreak and dead before supper. This “new sickness” as it was called, played with its victims, who might linger for days, sometimes weeks. The chronicler Charles Wriothesley, noted,

“This summer reigned in England divers strange and new sicknesses, taking men and women in their heads; as strange agues and fevers, whereof many died.”

As I write this in the spring of 2021, the range of symptoms reported in this epidemic of the late 1550s — chills and fevers, a grievous pain of the head, heaviness, difficulty of breathing, hoarseness, loss of strength and appetite, restlessness, a terrible cough which became so violent that many were in danger of suffocation —are chillingly familiar. It is thought that a strain of flu was responsible. This was not the first suspected flu epidemic on record — a somewhat milder sickness hit England in 1510. But this time the effects were devastating. It could not have come at a worse time. The Devon historian Hoskins tells us that continual rain had resulted in disastrous harvests in 1555 and 1556, the latter, he says, the worst in living memory. Famine no doubt contributed, but flu was probably the main cause of high mortality all over the country. Even after a better harvest in 1558, people continued to die in large numbers.

For a few years the steady increase in England’s population evident throughout the sixteenth century was halted. Experts use various data to establish death rates, including the number of wills proved and burials recorded in parish registers. Both make stark reading. For example, according to Hoskins, in the diocese of Worcester the average number of wills proved from 1551 to 1555 was 135 a year. For the years 1556 to 1558 the average was 530, a fourfold increase. In 1538 Thomas Cromwell was behind a law that required parish priests to record births marriages and burials. But adherence was so patchy that Elizabeth 1 passed another law on her accession in 1558 and many parish registers start from that date.

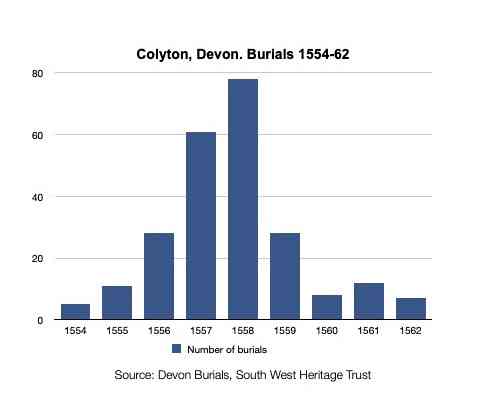

In Colyton in East Devon, however, the registers were meticulously completed from 1538 and have survived to tell a grim story. Burials in the parish in 1557-1558 were three and a half times the normal level.

Across England scarcely a family was untouched, leaving few to till the land and garner the next harvest. Drawing on contemporary sources, Strype in his Eccesiastical Memorials, published in 1820, but compiled a centruy earlier, says:

"In some places corn stood and shed on the ground for lack of workmen. In the latter end of the year. quartan agues were so common among men, women, and young chldren also, that few houses escaped..........."

It might be argued that this epidemic changed the course of history. When Calais came under a surprise attack in December 1557 the Earl of Rutland, charged to lead an expedition to reinforce the garrison there, found fit men were hard to find. By the time he arrived it was too late.

The “new sickness” was no respecter of status. During the autumn of 1558 a new wave began to move north, reaching London around mid-late October. Queen Mary had been in poor health for some time, but flu is thought to have contributed to her death on 17 November 1558. Within twelve hours Reginald Pole, Archbishop of Canterbury was also dead, folowed shortly after by two of Mary's physicians; all probable victims of the epidemic.

In some parts of England further waves continued during the next year but the danger time had, it seems, passed in Colyton. By 1560 recorded burials there had shrunk to numbers similar to those seen before the epidemic struck. But the disease continued its rampage on into Scotland where in 1562 the whole court, including the Queen, were suffering. Writing to Cecil in November of that year, Lord Randolph described the outbreak as

“A new disease, that is common in this town, called here 'the newe acquaintance,' which passed also through her whole court, neigh sparing lord, lady, nor damoysell, not so much as either French or English. It is a pain in their heads that have it, and a soreness in their stomachs, with a great cough, that remaineth with some longer with other short time, as it findeth apt bodies for the nature of the disease…”

Perhaps the sickness had lost some of its potency, for Randolph adds:

“There was not an appearance of danger, nor manie that died of the disease, except some old folks.”

Mary Stuart spent six days in her bedchamber.

It has been suggested that this may have been the first truly global pandemic to be recorded, although another outbreak in 1580 also claims that title. Medical knowledge was rudimentary. As for PPE in those days, well, some doctors may have adopted the rather frightening costume of the seventeenth century plague doctor.

A beak like mask co ncealed a compartment stuffed with sweet smelling herbs such as lavender, dried flowers, sometimes a vinegar sponge, and other aromatic items like juniper berries, cloves, ambergris, and labdanum, a resinous extract from some species of rock rose. Breathing through these would, they believed prevent infection, suggesting some understanding of airborne spread.

ncealed a compartment stuffed with sweet smelling herbs such as lavender, dried flowers, sometimes a vinegar sponge, and other aromatic items like juniper berries, cloves, ambergris, and labdanum, a resinous extract from some species of rock rose. Breathing through these would, they believed prevent infection, suggesting some understanding of airborne spread.

These must have been terrifying times indeed. On top of the terror of this new pestilence, other killer diseases remained rife. In 1562 Queen Elizabeth 1 famously recovered from smallpox. Many did not. Then, in 1563, London was beset by one of the worst outbreaks of plague in living memory. By some estimates it killed more than twenty percent of London’s population.

Cases of the plague continued into the autumn and, on 30 September 1563, Queen Elizabeth ordered strict quarantine measures. All houses with infected individuals had their doors and windows boarded up and no-one inside was allowed contact with anyone outside for 40 days. Cases dropped by thirty percent in the first week after quarantine was introduced, and continued to fall as winter progressed.

Life was uncertain in sixteenth century England. Our own certainties have been severely challenged during the extraordinary time of COVID. As we move cautiously out of our own pandemic, let’s spare a thought for those who went before us.

W. G. Hoskins - Harvest fluctuations in English Economic History 1480-1619

Thomas Wright - Queen Elizabeth and her Times (1838)

John Strype - Ecclesiastical Memorials, Relating Chiefly to Religion, and the Reformation of It, and the Emergencies of the Church of England, Under King Henry VIII, King Edward VI, and Queen Mary

Loved this post? Don't forget that you can click the links below to share on your social media.