Lifting the veil that separates us from times long past - St. Thomas a Becket, Bridford, Devon

Devon’s churches have stood sentinel over the lives of countless generations and remain to give us a unique window into forgotten times. Stonework, windows, roof timbers, magnificent carvings, glorious painted rood screens, fonts and pulpits, monuments, memorials and gravestones - all evoke a strong spirit of place and have echoes of past lives. Many of these ancinet buidlings have hardly changed since those masons and carpenters laboured long to create such enduring beauty. As a writer I spend a lot of time exploring these wonderful survivors, walking in the footsteps of those who went before, absorbing the hallowed, musty atmosphere and marvelling at the skills of medieval craftsmen.

Occasionally I am able to visit a church while wearing sixteenth century clothes, and then the veil between me and the past becomes gossamer thin. As I glide down the aisle the hairs on the back of my neck begin to stand on end. So it was when I visited Bridford, high up in the Teign Valley, on a drizzly November day. After, giving my talk, or rather the Lady Katherine’s “audience”, to a small but lively meeting of the local WI, I walked the short distance to the church of St Thomas a Becket.

I’d come across the village in my research for A Woman of Noble Wit. The Champernowne family held the manor and advowson of Bridford as part of the Valletort inheritance which came to Richard Champernowne in the early fourteenth century. Close to the moor, it may well have been a favourite site for a hunting lodge. John Champernowne of Modbury, grandfather of the heroine in my novel, presented to the church in 1473 and 1498, and her father Philip also did so in 1508. Bridford remained part of the family estates until, in the early part of the seventeenth century, another Sir Richard Champernowne sold the title to the manor to Sir Simon Leach.

The name means 'brides' ford, a place where the river was shallow enough for a bride to cross. It’s only nine miles south west of Exeter but even today Bridford feels a bit isolated. Hoskins tells us that, according to the rector, when Napoleon’s invasion threatened, the well-to-do of Exeter made plans for flight to Bridford, as though it were on another continent. It was not sufficiently isolated, however to escape the plague, which in 1591 saw seven members of the same family buried in seven weeks between August and October.

The parish register records those deaths and also includes the following reference to the 1549 "Prayer Book Rebellion", the events of which feature in my novel:

“The malcontents assembled to the number of 10,000 under Arundel besiege Exon. Defeated by John Lord Russel.”

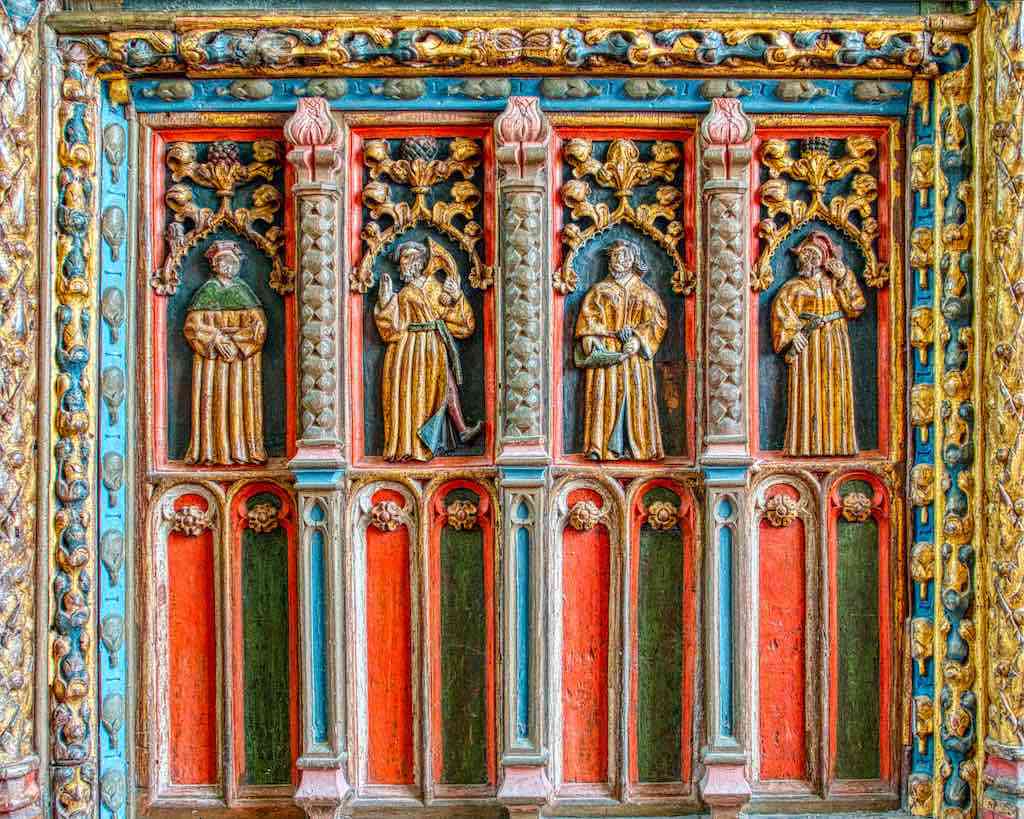

I am drawn towards the magnificent rood screen which was most probably erected in the early part of the reign of Henry VIII, when Walter Southcote was vicar. His initials are traced on the screen along with carvings of a double rose and pomegranate, devices of the King and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Southcote’s death in 1550 is recorded in the parish register near the entry about t he Commotion Time given above.

he Commotion Time given above.

Some of the figures on the screen hold wind instruments. Sir Philip Champernowne of Modbury was renowned for the fine musicians and singers he kept at Modbury Court, a tradition that the Champernownes continued for several generations. It is tempting to imagine that Sir Philip, with his love of music, was responsible for choosing those images.

Beyond the screen, a wonderful surprise awaits. On the reverse of the wooden panels is an astonishing group of monochrome paintings, known as ‘grisaille’. They may be figures from a popular morality play called ‘Mundus et Infans’ (The World and The Child) which shows the progression of a man’s life from sin to repentance.

The Champernowne’s Manor of Ashton Rohant was not far from Oxford where a bookseller records the sale of a manuscript edition of “Mundus et Infans” in 1520. Wynkin de Worde produced the first printed version two years later. Is it possible that Sir Philip, by all accounts a well educated man, could have had a copy?

The group seems to be under the direction of a man dressed in Turkish style robes. Perhaps he is meant to represent one of the King’s who in the play represent temptation and the seven deadly sins. Of course, King Henry VIII often adopted Turkish style robes in his “disguisings”, so perhaps that explains why this man is so dressed. Or perhaps it was just the convention of the time.

But Sir Philip’s son John visited the court of “The Great Turk” in around 1540 on a secretive mission with his cousin Peter (later Sir Peter) Carew. They were apparently disguised as merchants and King Henry VIII financed their journey. Sadly, on their way home, John Champernowne, his cousin and a companion contracted a severe illness, from which only Peter Carew recovered. Am I being fanciful to think that Sir Philip might have asked for those Turks robes with his son in mind?

As I stand in the silent church on that gloomy Devon afternoon I am transfixed by those figures. One has his head thrown back, draining a flask, one is a woman, one wears a workman’s smock, but it is the man in doublet and fine hat who holds my gaze. His arm is held high, as if in greeting, and he seems to look right into my eyes. Shivers run down my spine as I stare back at him …………….

If you have enjoyed this post don't forget to share it on your social media using the buttons below.