Names - the frustrating vagaries of sixteenth century spelling!

Anyone who has researched their family history will be familiar with the frustration of finding, or more often missing, different spellings of their family name as they trawl through parish registers, wills and land transactions. We are lucky to have access to sophisticated search engines and online catalogues, but it is so very easy to miss vital documents. The further back you go, the worse if gets. Amongst the records that remain to us from the sixteenth century and before, its an absolute minefield! So when searching for records that mention the characters in A Woman of Noble Wit I took care to search under every possible variant spelling.

These lists are not exhaustive but, to illustrate, I found the Champernowne’s as, Champernon, Champernowne, Champernoun, Chamborn, Chambernon, Champnon, Champnone, Champernulph, Chamber, Shamborne, and even Di Campo Arnulfo. The Giberts crop up variously as Gilbert, Gilberde, Gilberd, Gilbard, Ghylberd, Ghylbert, Gylberd, Gylberte.

Don’t get me started on the Raleigh’s!

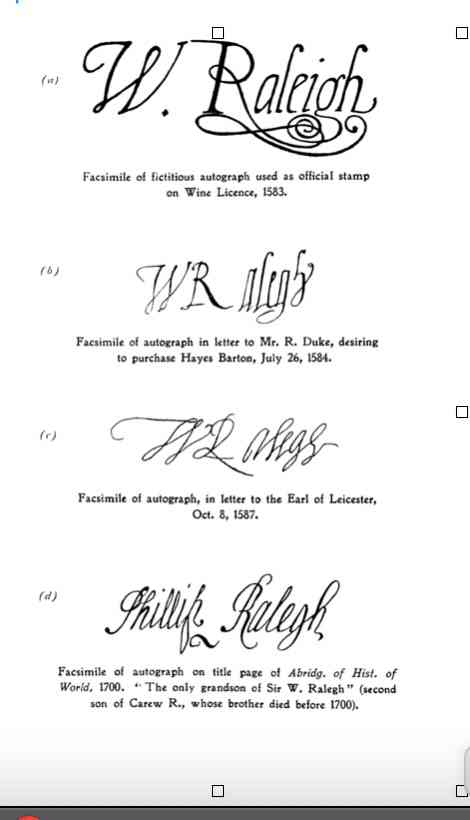

Stebbing, an early biographer fo Sir Walter, claims to have found around seventy variations. The collection of three signatures on the left -two used by Sir Walter himself and one by his grandson, - are among the examples given in a paper by the nineteenth century scholar T N Brushfield.

Stebbing, an early biographer fo Sir Walter, claims to have found around seventy variations. The collection of three signatures on the left -two used by Sir Walter himself and one by his grandson, - are among the examples given in a paper by the nineteenth century scholar T N Brushfield.

To add to the confusion different spellings even appear in the signatures of different family members in the same document. For example, tithes of fish were leased by the manor of Sidmouth to ‘Walter Rawlegh the elder’ ‘Carow Ralegh’ and ‘Walter Ralegh the younger’ in a deed dated September 10, 1559. In 1578 the same persons passed over their interest in the fish-titles in another deed, which contains their signatures. They had clearly still not decided how to spell their name. This time the father writes his name as ‘Ralegh,’ his elder son Carew as ‘Caro Rawlyh,’ while young Walter calls himself ‘Rauleygh. To add another layer of confusion, Sir Walter, a prolific letter writer, used many variants during his lifetime.

Mathew Lyons, Historian and Author of “The Favourite,” a fascinating look at Sir Walter’s extraordinary relationship with Elizabeth 1, has an interesting article on the spelling of Raleigh’s name on his website - find it here.

So what on earth is going on, and where did those names come from anyway? In England before the Norman Conquest, people did not have hereditary surnames: they were known just by a personal name or nickname, or by their trade or place of birth. After 1066, the Norman barons introduced surnames into England, and the practice gradually spread. Initially, the identifying names were changed or dropped at will, but eventually they began to stick and to be passed on.

By the sixteenth century, trades, nicknames, places of origin, or fathers' names had become fixed surnames. But these names were not actually written down very often. It turns out that consistent spelling of surnames did not really settle until at least the seventeenth century. Often the spelling depended on the level of education and the whim or the writer, whether that be the parish priest, a lawyer, the person themselves, or whoever was writing to them. Often the spelling is phonetic - something that sounded near enough would do - the reader could work it out!

First names can be just as confusing. Only a limited number were in use, and families tended to repeat them often, so we find fathers and sons, brothers, cousins and uncles, all bearing the same first name within a generation, and the spelling is wildly varied. For example, Katherine’s first husband, who I have called Otho, and his grandfather of the same name, can be found in source documents as Otes, Otys, Otto and Otho.

For girls Katherine was a very popular name in the fifteenth century, and became even more so after Katherine of Aragon married Prince Arthur of England in 1501. There are many Katherine’s in my story - three queens, a grandmother, a mother a sister, a great aunt, a sister in law, a daughter, and my heroine, all have the same name. The spelling of first names is also highly variable, and “Katherine” is no exception. The use of a K or a C at the start seems to have been interchangeable. The name may have been pronounced with a hard “t” and written as “Katryn “ - the spelling adopted by Kat Ashley in her 1536 letter to Cromwell.

The task of the researcher is a hard one indeed!