Exeter Cathedral

“She took a faltering step forward, tipped her head back and gazed, unblinking, at the soaring columns and the vaulted ceiling with its gaily painted bosses. Goosebumps slid down her neck and along her arms as she slowly released her breath. It was like being in a stone forest, with branches entwining high above. Near dazzled by the light from so many windows, she was in a new world full of gaudy colour and light. She felt like a tiny, insignificant speck as the vast cathedral cast its spell over her, and sank to her knees on the cold stone floor.”

An extract from A Woman of Noble Wit

The year is 1528 and Katherine Champernowne, a young girl brought up in the small market town of Modbury, enters the great Cathedral of St Peter in Exeter for the first time.

We can only imagine how a girl like Katherine would have felt as she stepped into this magnificent cathedral. I have visited many times, for services, concerts when the voices of choirs like The Sixteen soar to the heavens, and simply to wander in this special place and soak up the atmosphere of the centuries. Like Katherine, I have felt goosebumps running down my spine. I am swept away anew every time.

How much more impressive mus t it have been in the late fifteen twenties, when most people lived in poorly lit, draughty, dreary buildings, struggling to keep body and soul together? A well born girl like Katherine might have been used to seeing the Great Hall at her home, the Court House, well lit by candles instead of rush lights. Her family were wealthy enough to add colour to their living space with tapestries and paintings. There may have been some larger widows to let in the light. But even she would have seen nothing to equal the splendour of the Cathedral with sunlight spilling though its many windows, casting patterns all around.

t it have been in the late fifteen twenties, when most people lived in poorly lit, draughty, dreary buildings, struggling to keep body and soul together? A well born girl like Katherine might have been used to seeing the Great Hall at her home, the Court House, well lit by candles instead of rush lights. Her family were wealthy enough to add colour to their living space with tapestries and paintings. There may have been some larger widows to let in the light. But even she would have seen nothing to equal the splendour of the Cathedral with sunlight spilling though its many windows, casting patterns all around.

Before entering Katherine would have passed the West Front Image Screen with its rows of carved and brightly painted statues set in niches. Added in 1340 the screen completed the re‑building of the cathedral in the Gothic style. Work continued until the additional top tier was completed about 1470. So it must have looked new and astonishingly bright in 1528.

She would surely have found it just as breathtaking as I do to look up at the stone vault that makes up the ceiling of the nave and quire. Dating back to the fourteenth century it is the longest continuous medieval stone vault in the world — a distance of approximately 96m (315ft). It runs all the way from the West wall of the nave to the Great East Window at the far end of the quire.

Katherine might have raised her eyes to the minstrels gallery, built in the mid 14th century. Perhaps its carved angels playing musical instruments, would have reminded her of her father’s fine players and singers at Modbury.

Katherine might have raised her eyes to the minstrels gallery, built in the mid 14th century. Perhaps its carved angels playing musical instruments, would have reminded her of her father’s fine players and singers at Modbury.

A well educated girl, she might well have marvelled at the large dial of the Exeter Astronomical Clock — a working model of the solar system as it was understood in her time. The sun and moon circle around the earth at the centre of the dial. The door below would have been there, but the hole not yet cut for the Bishop’s cat to come and go.

On my last visit I paid my respects to members of Katherine’s family remembered within the cathedral's walls.

In this splendid monument Katherine’s uncle, Sir Gawen Carew lies beside his wife. The other figure is Sir Peter Carew, son of Katherine’s uncle George, who rose to prominence in the church under King Henry and his son, Edward, managed to keep a slim hold on his position through Mary’s reign, despite his marriage, and returned to high favour under Elizabeth, officiating at her coronation.

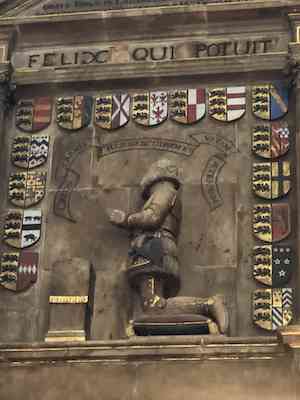

And here is the memorial to Katherine’s cousin, another Sir Peter Carew, erected by Exeter antiquarian John Hooker, to commemorate his former patron. Hooker also wrote a biography of Sir Peter who was a true Elizabethan adventurer.

Below stands the tomb of Katherine’s eldest son, Sir John Gilbert, lying in splendour beside his wife, Elizabeth Chudleigh, with the arms of both families prominently on display. At his foot sits a rather endearing squirrel, the Gilbert family emblem.

Katherine herself does not lie here. She and her second husband, Walter Raleigh senior, lived out their twilight years in Exeter in a house “close by the Palace Gate”. Walter senior was buried in old St Mary Major’s when he died in 1581, and it is believed that when Katheirne herself died in 1594, she was re-united with him there. We only have a transcript of her last will, made in April of that year, the original having been lost in the World War 2 bombing raid that damaged the Cathedral and scored a direct hit on the City’s archives. It is thought that she died soon after making her will, but unfortunately the very page from the parish register that would have included details of her burial is missing — damaged or lost.

Katherine’s youngest son, Sir Walter, in a poignant letter to his wife in December 1603 — when he expected to die very soon — asks that his body to be laid at Sherborne or “in Excester church by my father and mother”. This is taken to mean St Mary Major. The old church was demolished and replaced in Victorian times. The replacement also fell into disuse and was pulled down in the 1970s So, the nearest I can get to the place where Katherine and her Walter lie is this cross on Cathedral Green which marks the site of old St Mary Major church. It is all that remains.

Katherine’s youngest son, Sir Walter, in a poignant letter to his wife in December 1603 — when he expected to die very soon — asks that his body to be laid at Sherborne or “in Excester church by my father and mother”. This is taken to mean St Mary Major. The old church was demolished and replaced in Victorian times. The replacement also fell into disuse and was pulled down in the 1970s So, the nearest I can get to the place where Katherine and her Walter lie is this cross on Cathedral Green which marks the site of old St Mary Major church. It is all that remains.