Farthingale Sleeves

I’ve always wondered how those huge sleeves worn by Queen Elizabeth 1 in all those fabulous paintings were created. Those sleeves were part of an elaborate ensemble designed to display the Queen’s magnificence, as seen here in the Armada portrait.

I’ve always wondered how those huge sleeves worn by Queen Elizabeth 1 in all those fabulous paintings were created. Those sleeves were part of an elaborate ensemble designed to display the Queen’s magnificence, as seen here in the Armada portrait.

In the later years of Elizabeth’s reign similar voluminous sleeves were an important part of court fashion. Ladies like Sir Walter Raleigh’s wife, Bess Throckmorton — pictured here in 1595 — wore these rather uncomfortable looking sleeves, which must surely have restricted their arm movement considerably.

I had assumed that these sleeves were heavily padded, but when I was pattern testing with my friends at the Tudor Tailor I discovered that it was a bit more complicated than that. The sleeves were supported by a series of hoops, just like a farthingale skirt — hence the name — farthingale sleeves.

When elite women started to wear stiffened bodies and farthingales they were made by tailors, but soon specialist bodie and farthingale makers set up shop in London. In my quest to understand the work of these artisans and makers, I hand stitched my farthingale sleeve supports throughout. I used split willow cane which was sometimes used at the time, although by the 1590s whalebone was becoming more widely available and records suggest was often used in bodies, farthingale skirts and sleeve supports.

Making these farthingale sleeve supports — foundation garments to be worn under and hold out a rich fabric over-sleeve — really was an engineering project.

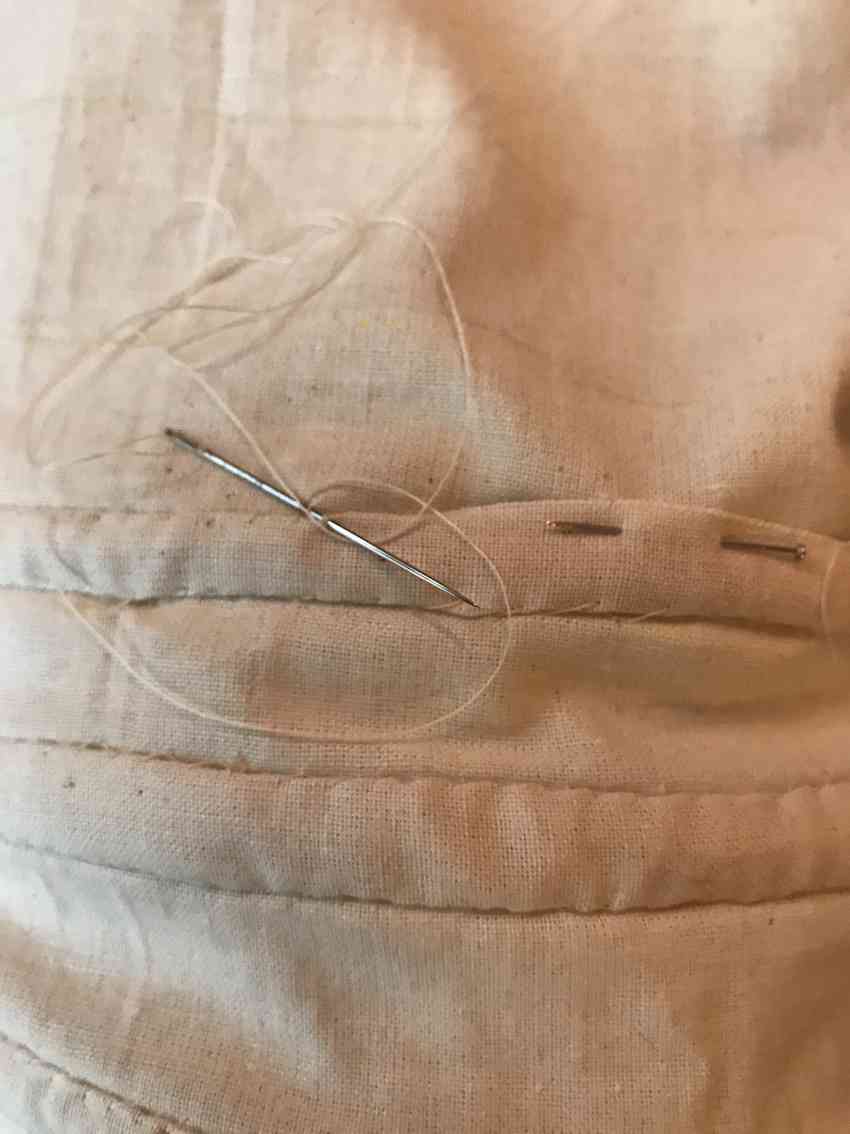

The measurements of the strips of cane had to be accurate, each one slightly larger than the previous one, all cut to the dimensions of a shaped casing cut from sturdy fabric. The cane strips are then joined firmly with linen thread to form a ring

i

and then slip-stitched into position on the fabric casing, the long underarm seam of which has already been closed.

It was a tricky and time consuming process, hard on the fingers.

The resulting structure looks rather like an elephant’s trunk, or the hose of a tumble dryer.

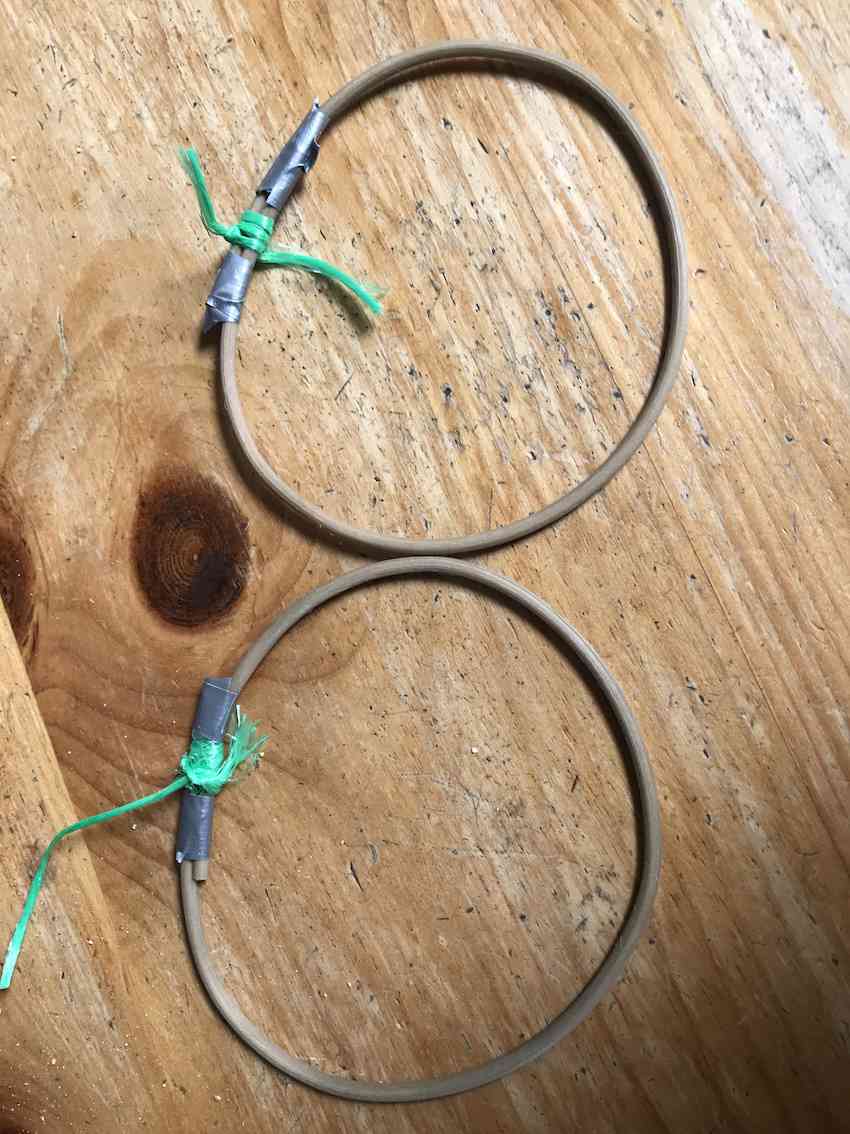

Separate hooped sleeve-head supports are also needed to make the sleeve stand out at the shoulder. These were very simple to make .

Round cane lengths are soaked overnight in water a nd then bent into a hoop, secured and left to dry. When the joining threads are removed the cane keeps its hoop shape and can be fitted into a fabric piece as shown.

nd then bent into a hoop, secured and left to dry. When the joining threads are removed the cane keeps its hoop shape and can be fitted into a fabric piece as shown.

These sleeve supports are added at the top of the sleeve to hold the outer sleeve cover, which I have yet to make, out from the shoulder. I hope soon to get to work on my 1590s gown which will use these farthingale sleeve supports under a covering of silk.

Detailed instructions for making farthingale sleeves will be included in the Tudor Tailor’s new book - The Typical Tudor - coming soon.