Dartington Hall

Dartington Hall, with its mellow grey stone walls, glorious gardens full of birdsong and ancient trees, is a favourite Devon gem I return to again and again. Set in rolling south Devon parkland near Totnes, it is now a stunning centre of heritage, culture, entertainment, hospitality and innovative sustainability.

The medieval hall, together with the Grade II listed garden that wrap around its grey stone walls, evoke a strong sense of times past and an air of peace and tranquility. What we see today has been shaped by many hands, a legacy of many owners, some forgotten, some stellar figures on the stage of history.

Why here?

This favoured spot, set high above a bend in the River Dart, has been occupied since ancient times. Before the weir was put in at nearby Totnes, Dartington marked the highest point of the tide, a strategic advantage for anyone holding the land. The first fording point where animals might cross was at Staverton, a short distance away. Once the thickly wooded river banks were cleared the soil proved fertile. So it’s not surprising that through the ages people have made their homes here.

Traces of Bronze and Iron Age dwellings and earthworks have been found in the fields that now make up the Dartington estate, some 1200 acres that now surrounds the Hall. As the Anglo Saxons swept into this part of Devon farm settlements were established in the valley bottoms.

One of these farmsteads clearly flourished. The first written record of Dartington comes in AD 833, when it is mentioned in a Royal Charter of Egbert, King of the West Saxons The registers of Shaftesbury Abbey show that the Saxon Lady, Boergwyn, one of three sisters, gave up her share of their joint inheritance — lands in a place known as Wennland — and retired to Dartington. It seems it was already a place suitable for a lady of substance. It's not certain exactly where Boegwyn made her home. It may have been a timber-built house set in enclosed riverside meadows, nearer the river than the site of the present Hall.

The Normans who held the estate

After the Norman conquest William of Falaise, a captain in William the Conquerer’s army, was the first of a succession of Norman lords to hold the manor. At the time of the Doomsday survey there was enough land to support fifteen plough teams, whereas most settlements in Devon could support no more than five. So Dartington was one of the most prosperous settlements in the county, a jewel amongst the nineteen manors granted to William of Falaise.

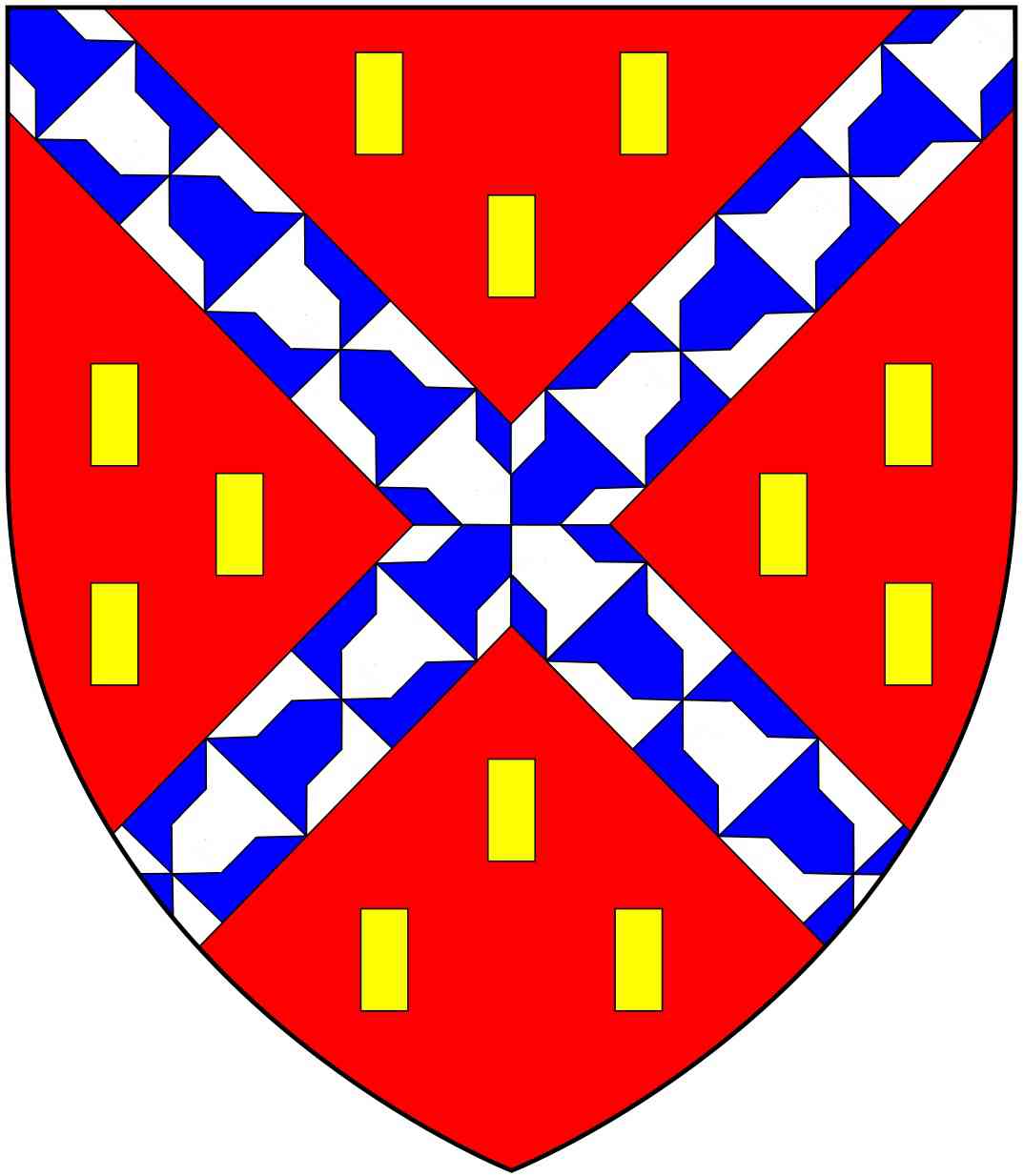

After William's death the estate went to his wife’s son from her first marriage and that began the occupation of the Martin, sometimes known as Fitz-Martin, family. The Martins held Dartington for eight generations from the early twelfth to the mid fourteenth century, more than two hundred years. Sir Nicholas Fitz-Martin, a supporter of Henry III, expanded the Martins’ land holdings both in Devon and Wales.

The church may have been built around this time. The Gate House and the Longbarn, now the Barn Cinema, are thought to be from around 1230, although its also been suggested these buildings may have Saxon origins.

Only the tower of St Mary's church survives

Sir Nicholas’ grandson William, Lord Martin, spent more time in Devon than his predecessors and may have added to the buildings around the present site. In 1326 the estate covered nine hundred and sixty-eight acres, including an enclosed deer park of one hundred acres. The pale and ditch of the deer park, can still be seen today near the eighteenth century wall that follows the line of the earlier pale. For want of a direct heir, the estate eventually passed to the Audley family for some twenty-five years. In 1385 it reverted to the crown and was granted to John Holland.(Some records show the name with one 'l' some with two.)

John Holland, First Duke of Exeter - half brother of a King

John Holland ( the name is spelt with one 'l' in some sources, with two in others) was the third son of Thomas Holland,1st Earl of Kent, and Joan, known as “the fair maid of Kent”. Joan, the daughter of Edmund of Woodstock, one of King Edward I’s sons, married Thomas Holland when very young and bore him two daughters and two sons, Thomas and John. It's said that the marriage was kept secret from her parents who had lined up another suitor. After Walter Holland's death Joan married Edward, the Black Prince. When he died in 1376 their son, Richard, became heir to Edward III's throne. He was only ten years old when he became King Richard II.

Played out in the aftermath of the Hundred Years War, against the background of the Peasants Revolt and the shifting allegiances of Richard’s troubled reign, Holland and his half-brother had what might be described as a difficult relationship. Its said their differences eventually caused their mother to die of grief.

Richard II granted Dartington and a number of other estates to Holland. However, his title to the lands was withdrawn soon after. This may have been because Holland was close to the King’s Uncle, the enormously powerful John of Gaunt. In 1386 Holland married Elizabeth of Lancaster, Gaunt's daughter, and joined her father on an expedition to Spain. On Holland’s return to England in 1588 King Richard made him Earl of Huntingdon and confirmed the lands granted to him before he went to Spain, including Dartington. That is when he set about building the magnificent hall complex that can still be seen today.

The buildings the Martins had occupied, perhaps neglected during the Audleys’ short tenure, were reported to be in a very bad state of repair. A man of John Holland’s prominence would, in any case, need a much larger, much grander establishment. Building work had started by September 1388, when the Dean and Chapter of Exeter granted slate from their quarry at Staverton. This was probably used to roof temporary buildings while the permanent structures were under construction.

The emblem of Richard II, the chained White Hart, which can still be seen on the central boss of the porch vault was not adopted by the King until 1390, so the hall must have been completed after that date. The wheat ears beneth the White Hart emblem are John Holland’s insignia as Earl of Huntingdon. By placing the White Hart emblem on the wheat ears in this way, Holland was perhaps demonstrating his support for his half-biother, the King.

Holland built his great hall with a hammer-beam roof similar to the one built for Koing Richard at Westminster Hall. This type of roof was a relatively new way of achieving a much larger span than one piece of timber could allow. John of Gaunt also had a hammer-beam roofed hall at Kenilworth, now sadly in ruins. Perhaps the success of his uncle’s hall and Holland’s newly constructed one at Dartington encouraged King Richard to have an even larger roof span at Westminster, whihc was completed a few years later.

To build such a hall in an unfortified mansion in remote Devon was quite a statement. He must have been very sure of his lofty status as a member of the extended royal family. Living chambers were added at one end of the hall, and at the other end, a spacious kitchen with several fireplaces and a high roof was built beyond a screens passage, buttery and pantry with accommodation above, perhaps for the steward. The kitchen now houses the White Hart Pub .

Holland may have felt secure enough to need no fortifications, but he did ensure that a large retinue of servants and men at arms could be accommodated on site by building residential quarters on two sides of the courtyard that faces the great hall.

The design of these two-storied lodging rooms, can still be seen in one that remains more or less intact today.

It's not known for sure whether the range of buildings glimpsed in the ruined arches that still stand to the south of the great hall was built by John Holland oris of a later date. Archeological investgations during the 1960s proved inconclusive.

Most of the work on Holland’s Devon country residence seems to have been completed by 1400, by which time King Richard had been deposed and Henry Bolingbroke, John of Gaunt’s son and Holland’s brother-in-law. That presented a dilemma for John Holland — should he continue to support his half-brother Richard, or should he fall into line under his wife's brother. After intially supporting Henry, Holland become embroiled in a plot to restore Richard, the Epiphany Rising. The plot failed and Holland was executed in January 1400. King Richard died, possibly murdered, at Pontefract Castle a few weeks later.

Holland’s estates and possessions were ceded to the crown but his widow managed to reclaim most of them, including Dartington a few years after his death. She was, after all, the sister of the new King Henry IV. Her son, John Holland II, spent part of his childhood at Dartington and went on to fight in France under both Henry IV and Henry V, including at Agincourt. After a distinguished military career he rose to become Admiral of England and was created Duke of Exeter in 1444. His son Henry Holland lived through the turbulent years of the wars of the Roses, a staunch supporter of the Lancastrian cause. He lost his life at sea at the age of forty-five in somewhat suspicious circumstances, with no heir to follow him. Eventually Dartington became a crown possession once again

A Royal “trophy” estate

It was useful for Kings and Queens of England to have properties they could bestow on people who had served them well, or those they wanted to keep sweet, and Dartington was a wealthy estate. So the estate was bestowedd on a succession of people who did not live there but took income from the manor. Those who benefitted in this way included Margaret Beaufort, mother of King Henry VII, and Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter who was the King's cousin. Two of Henry VIII’s queens, Katherine Howard and Katherine Parr, also took revenues from the estate, but never visited.

After Katherine’ Parr’s death in 1548 the estate was sold off and owners in came very quick succession, all taking advantage of a rapidly rising property market to make a speedy profit. In the late fifteen fifties John Aylworth reached agreement with Sir Arthur Champernowne to exchange Dartington for Polsloe Priory near Exeter ,

Sir Arthur Champernowne’s Elizabethan mansion

Sir Arthur Champernowne, a politician and soldier, came from a prominent Devon family and was an ardent supporter of the reformed way of religion. He had flirted with conspiracy under Mary Tudor, even spending a short time in the Tower of London after one of the plots against the Queen. He was riding high when Elizabeth succeeded Mary. One of his sisters, Katherine, married John Astley, a distant relative of Elizabeth's mother, Anne Boleyn. She is also known as ' Kat Ashely', and was Elizabeth’s childhood governess. Appointed First Lady of the Bedchamber when Elizabeth came to the throne, she remained an influential figure at the Elizabethan Court until her death in 1565. .

Miniature thought to be Katherine Astley, sourced via Wikimedia Commons

Queen Elizabeth appointed Sir Arthur Vice-Admiral of the Fleet of the West, a position that enabled him to support prominent Huguenot leaders during the French Wars of Religion.

Sir Arthur transformed the by now rather old-fashioned hall into a sixteenth century mansion, a suitable home for his family, with all the highest standards of comfort of his day. In his Survey of Cornwall, Richard Carew tells us that Sir Arthur designed a banqueting house for him at Antony in Cornwall, so we might assume that Sir Arthur took an interest in architecture and design. He might have looked for inspiration to the changes Edward Seymour, whose son married Sir Arthur’s daughter Elizabeth, was making at nearby Berry Pomeroy.

Sir Arthur and his wife, Mary Norreys (widow of his cousin Sir George Carew, who went down on the Mary Rose), probably also developed the gardens in the latest Elizabethan style, perhaps with knot gardens, arbours and walks. In the house he added more private bed-chambers, replaced old staircases, made changes to the rooms above the porch and undertook some modification of the accommodation on either side of the courtyard. It would be wonderful to imagine that he also created an Elizabethan long-gallery in the South courtyard where the arches now stand. Sadly, there is no evidence that he did. It is more likely that he actually dispensed with whatever crumbling buildings remained there from John Holland’s time. Many of Sir Arthur’s letters are written from Dartington, so it seems he spent a good deal of time in his Devon home until his death in 1578.

My fascination with sixteenth century Dartington and the people who lived there

Katherine Raleigh was another Champernowne sister and Sir Arthur is an important character in my novel A Woman of Noble Wit, whichis inspired by her life. He was the first of a long line of Champernownes at Dartington, Their fortunes as country landowners fluctuated but they never again realised the national prominence they had held in Elizabethan England. In 1925 Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst bought what was by then a dilapidated estate, What happened after that is a story for another day’s telling.

At present my interest lies firmly in the Dartington of the sixteenth century. Surely Katherine Raleigh must have visited her brother here? It has been suggested that her son, Sir Walter Raleigh, designed a water feature for Sir Arthur’s son, Gawen. (I'm still trying to track down a letter from Raleigh, said to be amongst the Champernowne papers.) If so, it seems the plan was never executed, but there is every possibility that Sir Walter did visit Dartington. Katherine’s other sons, Sir John, Sir Humphrey and Adrian Gilbert all lived nearby. At least two of Katherine’s boys, along with other cousins and relatives, accompanied her nephew Henry Champernowne when he led a force in support of the French Huguenots. Henry died at La Rochelle in 1570, but Sir Arthur continued to be a prominent champion and supporter of the Huguenot cause.

I am grateful to the Dartington Trust who gave me permission to film and take photographs in the grounds during my stay in November 2021, when I was researching my next novel, the Dartington Bride. I've also been allowed a peep behind ths scenes to locate a room known as "The Countess' Room, associated with one of Dartington 's ghost storeis. .

The Dartington Bride is the story of Lady Gabreille Roberda Montgomery, known as Roberda. She left war-torn France during the French Wars of religion to marry Sir Arthur's son Gawen. After the St Bartholomew's Day Massacre in August 1572, Sir Arthur welcomed Roberda's father, the Comte de Montgomery, and all of his family to Dartington as refugees. Later, when the Spanish Armada threatened England's coast, Sir Francis Drake visited Dartington. Gawen left him a ring in his will.

Garden tours

For some years now it has been my privilege to be one of a team of volunteers who lead tours of the Dartington gardens. I love sharing a little of what I have learned about this special place, the people who created it over the centuries and those talented individuals who throughout the twentieth century contributed to the design of the gardens we enjoy today.

Free tours of the gardens run every Friday at 11 am from March to October.

These are gardens for all seasons, and I’ve learned so much about the plants and trees that flourish here.

In the photo below I’m standing amongst the Spanish chestnuts that line the top of the tiered bank above what Leonard Elmhirst called the Tiltyard. They are thought to be around 400 years old. Almost back to Sir Arthur’s time.

If you've enjoyed this post please share on your social media, using the links below.