Catherine of Aragon - Tudor Style Icon and Power Dresser - Farthingales, blackwork embroidery and sumptuous fabrics

When fifteen-year-old Catherine of Aragon stepped ashore in Plymouth at 3 o’clock on the afternoon of 2 October 1501, she must have caused quite a stir. Imagine the scene when the lovely young woman walked down the gangplank, followed by her ladies, all dressed in the latest Spanish fashions.Townspeople jostled for spaces with the great and good of the West Country, hastily summoned to welcome the foreign princess who had travelled so far to marry King Henry Tudor’s heir. How impressed they must all have been by Catherine’s youth and beauty. Of course, everyone was also looking at what she was wearing.

By the time Catherine arrived, Plymouth had grown from a fishing village to become a bustling port with a population of 3,500. Devon ships carried cargoes of wool, cloth and tin to markets in France and beyond and brought back wine and other commodities.The well-to-do merchants and their wives, the local gentry and the ordinary people of the town who greeted Prince Arthur’s Spanish bride and her magnificent retinue must have been all agog. After all those years of conflict — what we now call the War of the Roses — followed by the reign of the rather dour King Henry VII, surely everyone was ready for good news. After a series of English-born Queens — Elizabeth Woodville, Anne Neville, Elizabeth of York — perhaps the Spanish Princess seemed a new celebrity, bringing with her a hint of the exotic. Think of Catherine and Arthur, her teenage husband-to-be, as the Kate and William of their day.

The people of Plymouth were only treated to the spectacle of Catherine’s arrival in their town by chance. Expected further along the coast at Southampton, her ship put into Plymouth after storms blew it off course. The townspeople greeted Catherine enthusiastically, as described in The Recyt of the Ladie Katherine, a fascinating account believed to be the work of a member of the King’s household who witnessed many of the events.

“The West Country’s nobility ‘with all goodly manner and haste sped themselves with right honourable gifts… saluted and welcomed her’”

The welcoming crowds may have been a little disappointed that as well as a coif (head covering) and hat, which allowed her ‘faire auburne’ hair to hang down about her shoulders, Catherine reportedly also wore a veil. But no doubt they marvelled at the multicultural entourage she brought with her. Her party included Spanish noblemen, both a chaplain and a confessor, a doctor, a secretary, a treasurer, a cup-bearer, six young Spanish girls ‘of gentle birth’ and two slave girls (probably Moors from Grenada). The party also included by musicians, minstrels and an acrobat who walked a tightrope.

Catherine’s Doctor, Licentiate Alcatraz, wrote that

“... she could not have been received with greater rejoicings, if she had been the Saviour of the World ,..”

Stepping safely onto English soil must have brought immense relief to the young princess, who had left her home at the Alhambra over four months ago and embarked on a challenging journey across Spain by land, followed by a perilous sea crossing. She had found a safe harbour, although the small port town set amongst green Devon hills must have seemed very different from Spain. Putting aside the exhaustion of her nightmare journey, Catherine went first to St Andrew’s church, which still stands in Plymouth. Its facade is hardly changed since 1501, despite severe bomb damage during Warol War II.

She remained in Plymouth for over a week while they unloaded everything from the ships, including part of her marriage dowry. The town audit books reveal a good deal of feasting laid on for her entertainment, including 6 oxen, 20 sheep, 2 hogsheads of Gascon wine, one of claret, and a pipe of muscadel.

Lord Willoughby de Broke, Lord Steward of the King’s Household, who had hurried from Southampton to Exeter, organised escorts of local gentry & nobles for her journey from Plymouth via Tavistock, Okehampton & Crediton, for her formal reception in Exeter. No doubt the people of Exeter also enjoyed the opportunity to take a peek at the princess while she stayed in their city. She spent several days there at the Old Deanery next to the Cathedral. Legend has it she was kept awake by the noise of the weathervane at the nearby church of St Mary Major. When she complained, they promptly sent a servant to the top of the tower to remove the vane.

She travelled on via Honiton, Crewkerne and Sherborne, until a month later her party reached Dogmersfield. There she met her father-in-law and future husband for the first time, before travelling on to be received in London. Dressed in Spanish style, her pretty hair hanging down her back beneath a coif the colour of carnations, topped by a little cap rather like a cardinal’s hat, she must have looked splendid.

Crowds lined her route across the country and heads turned everywhere she went. People packed the streets of London, enjoying the unexpected largess of King Henry’s magnificent celebrations, which included fountains running with wine. The wedding itself on 14 November was spectacular. Catherine and Prince Henry, dressed in silver tissue embroidered with gold roses, arrived at St Paul’s Cathedral’s west door, as trumpets sounded. Arthur appeared on a stage, also dressed in white satin. The Receyt mentions that Catherine and her ladies all wore Spanish costumes with

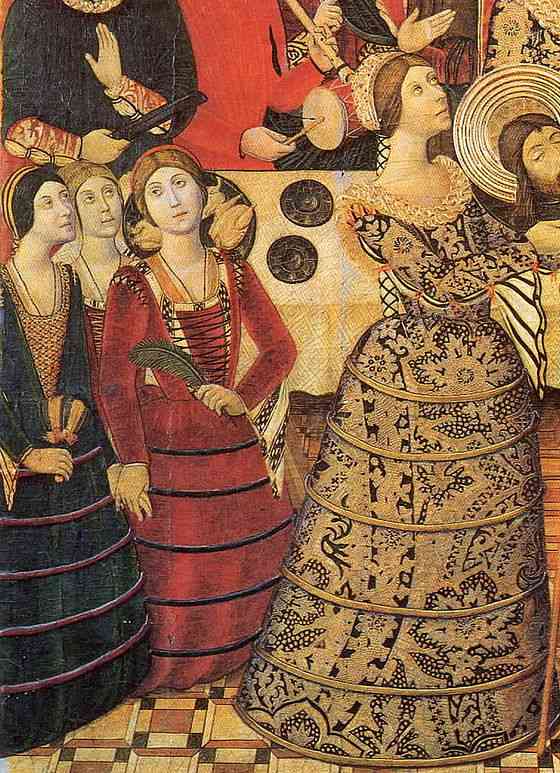

“ certayne round hopys berryng owt their gowns from their body’s after their country maner”.

This was probably the first time the people of England had seen the farthingale, perhaps with the hoops visible on the outside as in this early painting by Pedro García de Benabarre, (Salome from the St John Retable, Catalonia, 1470–1480. )

A week of festivities, tournaments and feasts followed the wedding, before Catherine and Arthur left for Ludlow, where they would make their home. Sadly, the young couple did not have long together. Catherine became a widow just a few months later. A long, uncertain, impoverished period followed when several times Catherine had to pawn her jewels and wardrobe in order to feed her retainers. But then, after his father died, in 1509, Arthur’s brother Henry, now King Henry VIII, made Catherine his first wife.

Farthingales

So what fashions did Catherine bring with her from Spain? Let’s start with that farthingale. The name comes from the Spanish word verdugado, (from verdugo — green wood) perhaps a reference to green osiers (willow withies) which bent easily into hoops, although esparto grass twisted into rope was used to stiffen earlier versions. Much later, whalebone came into use.

One suggestion is that Joan of Portugal, who married King Henry IV of Castile in 1455, was the first to use verdugados with hoops. Joan became notorious for her scandalous behaviour. As she had two illegitimate children by Pedro de Castilla y Fonseca, she was supposed to have used the farthingale to cover up a pregnancy. Whther that is ture or not, court fashion soon followed suit, and everyone added hoops to their skirts.

Having worn farthingales often, I’m not really convinced that they would have been effective in hiding a growing stomach. To do so, the hoops would need to sit much higher under the bust than in the picture above. The very heavy fabrics fashionable amongst the ladies of the Spanish court could provide a more plausible explanation. Rich silks woven and embroidered with metallic threads of gold and silver and sumptuous velvets were all the rage. Hoops may have provided support, allowing the ladies to put voluminous quantities of weighty and expensive fabrics on display.

By the time Catherine of Aragon left Spain, all the ladies of the Spanish court wore farthingales. However, it took some years for the fashion to really take hold in England. Catherine probably continued to wear one when, occasionally, she dressed in Spanish style. It was a useful way to underline her own royal lineage. Eleri Lynn informs us that in 1515, the Venetian ambassador recorded Queen Catherine as dressed richly in the Spanish style. At the famous Field of Cloth of Gold meeting, Catherine wore a Spanish-style headdress to underline her displeasure at the Anglo-French Alliance. But more often she seems to have made a conscious choice to adopt English styles to show herself as the English Queen and win over the people. She is most often depicted wearing the rather cumbersome English gable hood with her hair hidden.

A search of the records reveals only a few further mentions of the farthingale in the first half of the sixteenth century. For example, in March 1519, at a mask at Greenwich Palace, female dancers in fanciful “Egyptian” costumes wore black velvet gowns “with hoops from the waist downwards” which may have been farthingales. Later, the accounts of Princess Elizabeth in 1545 describe a farthingale made of crimson Bruges satin. When Anne Seymour, Duchess of Suffolk, asked for her clothes to be sent to her in the Tower of London in 1551, the list included a farthingale. Farthingales were certainly part of fashionable dress in England under Mary I, who bought and wore Spanish farthingales.

Mary Queen of Scots also adopted the style. Historical records show that she had a black taffeta “verdugalle” and another one made of violet taffeta, as well as a set of fashion dolls with 15 farthingales. Her wardrobe accounts show that she bought whalebone to shape he r farthingales in 1562. In contrast, whalebone does not appear in Queen Elizabeth’s wardrobe accounts until the 1580s. (Sarah A Bendall’s article “Whalebone and the Wardrobe of Elizabeth 1 has much more fascinating detail on the use of whalebone)

r farthingales in 1562. In contrast, whalebone does not appear in Queen Elizabeth’s wardrobe accounts until the 1580s. (Sarah A Bendall’s article “Whalebone and the Wardrobe of Elizabeth 1 has much more fascinating detail on the use of whalebone)

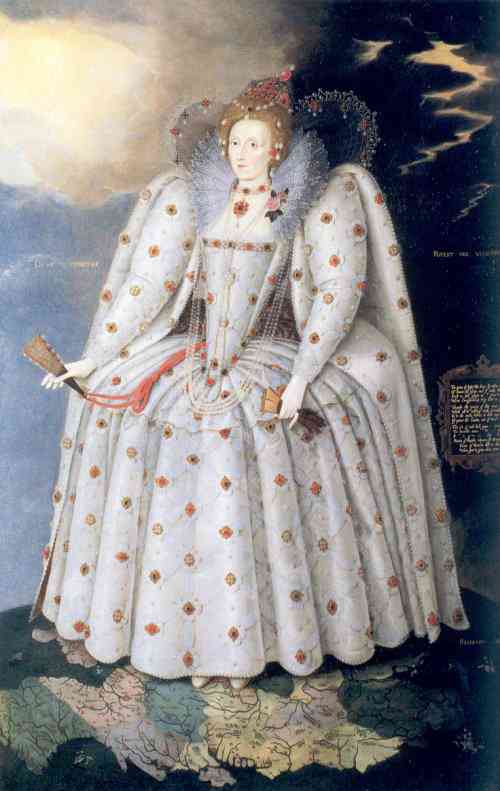

The French version, also known as the wheel or drum farthingale, replaced the Spanish farthingale, shaped like a bell, and characterises portraits later in Queen Elizabeth’s reign. With its intricate pleating and large sleeves, which were also often supported by farthingale type hoops, this fashion allowed even larger quantities of costly fabric to be on display. (See my video “Underpinnings” for more on reconstructing a French farthingale.)

Blackwork embroidery

It’s often said that another fashion trend Catherine of Aragon brought to England was blackwork embroidery. In the sixteenth century, the technique, which used black threads, usually silk, on white fabric, usually linen, became known as “Spanish Work”. But people in England knew about black embroidery on white linen before 1500. Chaucer describes the clothing of the miller’s wife, Alison, in the Canterbury Tales:

“Of white, too, was the dainty smock she wore, embroidered at the collar all about with coal-black silk, alike within and out.”

So, prior to Catherine’s arrival in England, people already applied black silk embroidery on smocks, also known as shifts. But there was certainly an explosion in the popularity of blackwork in the early C16. Before Catherine’s parents, Ferdinand and Isabella, conquered Spain, the Moors ruled the country. Their unique style of architecture included elaborate decoration using geometric designs. Tiles and patterns like those in the Alhambra in Grenada adorned the walls of the palaces where Catherine grew up .It was perhaps a particular style of blackwork, inpired by regular geometric patterns like those she remembered from her childhood home, that Catherine of Aragon made so popular.

Everyone wanted to copy her, so the use of this type of blackwork spread. Then, as now, young Royals set the fashion for everyone.

In portraits from the late C15 and early C16, a line of blackwork edging is often visible on the top of the undergarment (called a shift, a smock or a chemise) worn beneath the gown.

Tailors, most of whom were me, made outer garments for the wealthy. However, women made undergarments, shirts and shifts, and smaller items like cuffs and partlets. High-born women spent long hours embroidering these garments, which often featured in lists of gifts. For example, in 1563 at New Year Kat Ashley (nee Champernowne), gave Queen Elizabeth I :

“a night rayle wrought in black silk”

and a year later, she gave

“a smocke wrought with black silk only with a square collar”

Blackwork and similar reg ular patterns worked in red on white (red work) remained popular throughout the C16. Later designs became much more free flowing when flamboyant swirling patterns and floral motifs covered sleeves, doublets and coifs into the C17. More complex designs like those used on the Bacton Altar cloth, using a variety of stitches and colours to create intricate floral designs, became more popular towards the end of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, and the use of blackwork gradually declined.

ular patterns worked in red on white (red work) remained popular throughout the C16. Later designs became much more free flowing when flamboyant swirling patterns and floral motifs covered sleeves, doublets and coifs into the C17. More complex designs like those used on the Bacton Altar cloth, using a variety of stitches and colours to create intricate floral designs, became more popular towards the end of Queen Elizabeth’s reign, and the use of blackwork gradually declined.

Catherine and the power of clothing

People sometimes write off Catherine as the dowdy one who failed to produce an heir, the stubborn one who wouldn’t give up her position when she was too old to give the kingdom its heir. But when she first arrived she was young and pretty, having a fair complexion (naturally pink cheeks and white skin), rich reddish-gold hair that fell below hip-level, and blue-eyes. Her looks suited the idea of beauty favoured at that time. Contemporary sources suggest she was also a little on the plump side. Perhaps this was merely youthful roundness, seen as an attrative sign of future fertility.

Catherine was married to Henry VIII for far longer than any of the other wives, a marriage that in the early years seemed to be happy. Although she was older than her husband, they seem to have been a well-matched couple. Their intellectual tastes and educational background were similar. They both rode well and enjoyed hunting. They were both pious and studied theological works. Catherine had been born and brought up to be a queen and a powerful leader, like her mother, the formidable Isabella of Castile. When King Henry was fighting in France in 1513, Catherine, as his regent, took an active role in organising a campaign against the Scots. She won a famous victory and presented the King with the bloodied coat of the dead king of Scots. It is unfortunate that it is the one duty she failed to fulfil — the provision of a male heir — that so often defines her. If only one amongst all those pregnancies had produced a healthy son, how different things might have been.

Throughout her life, Catherine showed she understood the power of clothing. As we have seen, she adopted Spanish dress occasionally to underline her own independent royal status. She favoured dark colours, like purple, rich brocaded fabrics and cloth of gold, all of which enhanced her regal appearance. But under these queenly outer garments, it is said that Catherine wore the habit of a Franciscan nun.

Despite that nod to piety, she certainly knew how to dress to impress. When her nephew, the Emperor Charles IV, visited England in 1520, Catherine the Queen wore a petticoat of silver lamé, under a gown of cloth of gold lined with violet velvet with a raised pile, embroidered with the roses of England. Nor did she neglect her jewels. She wore a necklace of large pearls with a diamond cross hanging from it, and a black and gold headdress adorned with jewels and pearls. Her wardrobe also contained gowns of gold tissue, black tilsent (shot silk) decorated with Katherine wheels and a cloth of silver. She could easily match her husband’s passion for magnificence and display. It seems Catherine was not the dowdy frump she’s often portrayed as. But Henry needed an heir, and a younger woman, Anne Boleyn, had caught his eye.

When in 1527 Henry raised doubts about the validity of their marriage, Catherine immediately increased her clothing budget by 50%. Perhaps she thought to appear more attractive to the fashion conscious King, but dressing splendidly would also show that she, the Queen, outranked her rival. During the years she and Anne both remained at the same court, sharing the same household while Henry fought to dissolve his marriage to Catherine, the Great Wardrobe and the Royal jewels became a battleground.

Anne brought French fashions to the court and popularised the French hood, regarded as rather risque as it revealed quite a lot of hair. Catherine maintained a regal presence, continuing to act as though she were Henry’s wife and queen. Records show how Anne reacted angrily when she discovered a servant of the privy chamber taking linens to Queen Catherine for the King’s shirts. Catherine had continued to make and embroider Henry’s shirts, an intimate task that showed her wifely devotion. It seems Henry liked the shirts he was used to, for on this occasion, he intervened to confirm that he instructed the linen to be sent. Anne, however, ordered shirts made for the King to be sent via her in the future.

Even after Anne’s coronation, Catherine still projected herself as the rightful Queen and ordered new livery for her household embroidered with H and K. Labelled the Dowager Princess of Wales in 1535 Catherine persisted in giving out Maundy money, despite The King expressly forbidding her to do so.

During her banishment, she stimulated a cottage industry that produced household needlework. Women admired her for her dignity and perseverance, which inspired some to step out of their quiet roles as housewife to ply their needles and add to their incomes.

Ultimately, Catherine did not win the war. Anne took her place, albeit briefly. But Catherine undoubtedly had a powerful influence on what English women of wealth and status wore, an influence that lasted long after she had gone. Perhaps, after all, we should forget Anne Bolyn and her French hoods, and remember Catherine of Aragon as a real royal trend setter.

Rosemary Griggs

April 2022

Updated : 4 June 2024

Sources include

The Receyt of the Lady Catherine - edited by Gordon Kipling

Tudor Fashion - Eleri Lynn

Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlocked - Janet Arnold

The Elizabethan New Year Gift Exchanges 1559-1608 — edited by Jane A Lawson

‘Whalebone and the Wardrobe of Elizabeth I: Whaling and the Construction of Aristocratic Fashions in Sixteenth-Century Europe - Sarah. A Bendall, Apparence(s): Histoire et Culture du Paraître, Special Issue on ‘Modes Animales’, edited by Ariane Fennetaux and Gabriele Mentges (2022).

Shaping Femininity - Foundation Garments , the Body and Women in Early Modren England - Sarah A Bendall

Portraits

Catherine of Aragon - unknown artist - Lambeth palace

Catherine of Aragon by Michael Sittow- Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

Ditchley Portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger - NPG