Berry Pomeroy - searching for an Elizabethan lady

It’s not hard to understand why the ruins at Berry Pomeroy Castle are listed among the most haunted sites in England. Even on a bright March day the stone walls seem to hold echoes of the footsteps of those who walked here long ago. The ragged turrets reach up to a clear blue sky and sunlight streams through gaping holes where finely glazed windows once glittered.

But even in this clear spring light shadows of the past loiter around hearths that have lain cold for generations and skulk behind dark doorways.

Berry Pomeroy is one of those places where shivers run down your spine.

Devon was a dangerous place in the late fifteenth century as what we now call the Wars of the Roses divided families and led to vicious local feuds, most notably between the powerful Courtenays and the Bonvilles. High on a spur of land with steep slopes on three sides this must have seemed the ideal site for the Pomeroy family to build a fortified manor house; much safer, much more easily defended, than the vulnerable dwelling that stood next to the church of St Mary’s in the village. The gatehouse and part of the towering curtain walls they raised round their new home dominate the approach to the ruins today.

Its difficult to pinpoint the exact date of construction or which of the Pomeroys was responsible for building it, but Berry Pomeroy is reckoned to be among the last true fortresses built in England. The room above the gatehouse, with its faded wall painting depicting the adoration of the Magi, retains the feel of a place of worship. Perhaps the Pomeroys thought placing their chapel here would keep them safe. Perhaps they were right. The formidable defences were, it seems, never tested.

Most ghost stories and reports of apparitions centre around the romantic ruins of St Margaret’s Tower. Unfortunately the myths don’t really hold true. This tower was not a dank dungeon with a dark and troubled history. It was merely a gun emplacement covering the approach from the South and the gatehouse. But people continue to report strange feelings along the wall walk and in the tower.

It is not the tragic stories of Pomeroy women who supposedly met a grisly fate in this tower that have drawn me back to berry Pomeroy. I do not seek poor pretty Matilda Pomeroy, the White Lady, whose jealous sister Elinor is said to have shut her up in a dungeon below the chapel in the gatehouse (later versions of the story call her Margaret and the dungeon is supposed to have been in St Margaret’s Tower) and left her to rot. Nor do I look for the Blue Lady, a Pomeroy who is said to have strangled her child and was purportedly encountered by the physician Sir Walter Farquhar in the late eighteenth century. I am searching for traces of a different woman; a woman who lived at Berry Pomeroy during the reign of the first Queen Elizabeth when the powerful Seymour family transformed the Pomeroy’s fortress into a fashionable Elizabethan mansion.

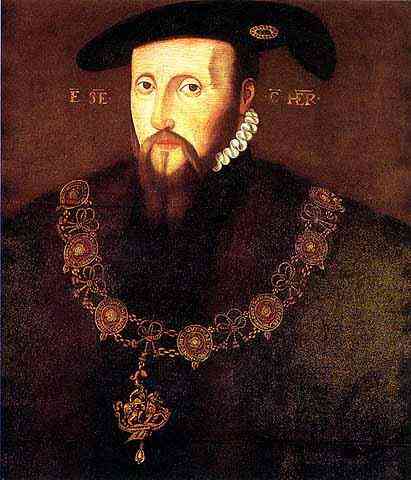

In December 1547 Berry Pomeroy was bought by Edward Seymour, first Earl of Hertford and first Duke of Somerset. Brother to King Henry’s third wife, Jane, Edward Seymour had become Lord Protector of his nine year old nephew, Edward VI, making him the most powerful man in England. Berry Pomeroy was his most valuable single acquisition as he gathered properties to bolster his wealth and aggrandise his new position.

Portrait of Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford (1537, later in 1547 created 1st Duke of Somerset & Lord Protector 1547–49); by unknown artist, Collection of Marquess of Bath, Longleat House, Wiltshire.

But he probably never set foot in this Devon jewel in his crown. Deposed in 1549 by his rival John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, Lord Protector Seymour was executed in 1552.

It was Seymour’s son by his first marriage, another Edward, who built a stylish Tudor house within the walls of the Pomeroy’s manor. But this second Edward, known as Edward, Lord Seymour, did not inherit his father’s titles and lands. Protector Somerset doubted that his first wife, Katherine Filliol, had been faithful to him. So he disinherited his eldest son, John, who died shortly after his father’s death in 1552, and the second son,Edward. The bulk of the Protector’s estates eventually went to the second family he had with Anne Stanhope. Edward Lord Seymour, his eldest surviving son, managed to secure Berry Pomeroy after a lengthy legal tussle, but little else. The preference of his half brother’s clearly rankled with him and the Berry Pomeroy branch of the family continued to dispute their inheritance for generations.

Between 1560 and 1570 Edward, Lord Seymour, replaced the Pomeroy’s domestic buildings with a four storey mansion in the latest “hunting lodge” style (rather like the one Nicholas Poyntz built around 1550 at Newark Park, Near Wotton-under-edge, Gloucestershire). The views from the upper floors must have been magnificent. Everything was designed to impress. The imposting facade that still stands bears testament to the grandeur of the place that became the home of the woman I am seeking.

Elizabeth Champernowne was the eldest daughter of Sir Arthur Champernowne of Dartington Hall and his wife Mary Norreys, (widow of Sir Arthur’s cousin, Sir George Carew, who went down with the Mary Rose). On 30 September 1576 Elizabeth married Edward Seymour II, son of Edward, Lord Seymour of Berry Pomeroy, who was possibly eight years her junior. Some sources suggest that the couple were first betrothed when Elizabeth was around 11 years old, and her intended was a child of only 3 or 4 years. It seems from letters in the Cecil collection that there were last minute difficulties in agreeing the marriage settlement. Apparently Lord Edward wanted Sir Arthur to include lands in the package on offer with his daughter. Sir Arthur offered 1000 marks, but not the desired land. They were still wrangling about the deal a week before the wedding, though it appears there had already been another, secret betrothal, unbeknown to Lord Edward. On 22 September 1576 Sir Arthur Champernowne requested “ Lord Burghley’s good offices with Lord Edward Seymour, whose son her wishes to match with his daughter”. All must have been resolved for the marriage took placer at Dartington a week later. We can only imagine what it must have been like for a young woman of 21 to be parcelled up with monies and lands so that she could marry a teenager of thirteen or fourteen she had known since he was a small child. Like most women of her class she had little choice in the matter. It was a marriage that brought important connections for her father, so Elizabeth left Dartington to join her husband at the magnificent house at Berry Pomeroy. The couple’s first child, a daughter named Bridget Margaret, was born in 1577. No doubt after her mother-in-law died in 1580, Elizabeth took up the reins and became mistress of one of the most prestigious houses in te west of England.

Though only a shell remains, it’s easy to imagine Elizabeth and her young husband enjoying a feast in the great hall while servants scurried in bearing food and drink from these doorways to the pantry and buttery across the screens passage.

Elizabeth must have walked along the paths of the terraced gardens created around the new building and looked down at the view over the river below.

Later, perhaps she and her husband pored over plans for the new wing.The idea was to make Berry Pomeroy one of the grandest country houses in the West country, a rival for the likes of Longleat. By this time the young man Elizabeth had married was playing a prominent part in Devon life. He was MP for the county in 1593, and again in 1601 and 1604; he also served as sheriff and Deputy Lord Lieutenant from 1595 to 1596 and was colonel of a militia regiment charged to defend the ports of Plymouth and Dartmouth. But it was his ambitious building plans that really singled him out as one of the leading men in the county.

Sadly little remains today of the grand staircase, ceremonial entrance and logia, long galleries, spacious bay windows, luxurious new apartments and extensive kitchens Elizabeth’s husband built. Building started around 1600 with a team of specialist masons working to a design based on classical patterns. Many of the masons left their marks in the stonework. Berry Pomeroy must have been a noisy building site for many years before Edward ran out of money and work ceased before his death in 1613, Even incomplete Elizabeth’s home was surely one of the finest in the west of England.

I can imagine Elizabeth living the life of a grand lady in this splendid mansion, walking in the long gallery in her fine gown or sitting in the spacious bay window with its views over the deer park and surrounding countryside.

But it is in the Church of St Mary’s in the nearby village that I finally track her down and discover the essence of her life.

At the East end of the North aisle, hemmed in by modern day furnishings, stands an overpowering monument. The figures carved here were described by architectural historian Nicholas Pevsner as “astonishingly naive.” “To think that the children of Lord Protector Somerset were satisfied by this” he commented. However, another Devon historian, W. G. Hoskins described the monument as “fine”.

Whatever its sculptural merits, it is the story this monument tells that I find most interesting. The topmost figure is Edward Lord Seymour, builder of the first Elizabethan house at Berry Pomeroy, Beneath him lies his son, Edward II, whose ambitious project to further enhance the property was never quite completed. These two are depicted in their armour under a cornice of roses and pomegranates. Below them lies Elizabeth, Edward II’s wife, daughter of Sir Arthur Champernowne — subordinate in death as perhaps she was in life — and below her are the figures of nine children, five boys and four daughters.

At Elizabeth’s head is a baby in a cradle, and at her feet a seated toddler — the children who did not survive infancy — in her hand she holds a prayer book.

Elizabeth’s life was, like many well-born women of her day, devoted to duty and serving her family and her God. As a mother she must have known many joys and many sorrows. In her enormously helpful History of the Champernowne Family, a document I often consult at the Devon Archives, Miss Champernowne suggests that Elizabeth probably died in childbirth.

Perhaps in this monument I have found the face and the true story of Elizabeth Champernowne, wife of Edward II Seymour of Berry Pomeroy .

You can find out more about Berry Pomeroy here

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/berry-pomeroy-castle/

or better still go along and see for yourself

If you’ve enjoyed this post do share it on social media by clicking the links below