Agnes Prest — Exeter martyr — Burned at the stake in Southernhay on 15 August 1557

Today Southernhay is a leafy street of attractive Georgian town houses and modern offices just beyond Exeter’s ancient city walls. It follows the line of the great town ditch, know as the Crulditch a name which, according to Devon historian Hoskins, comes from the word crull, meaning curly, as the ditch followed the curve of the city wall.

Photo from a copy that hangs on the wall of my office.

You might just be able to make out the name Crulditch on this map of the city which was commissioned in 1587 from the Flemish engraver Remigius Hogenberg by John Hooker, the first Chamberlain of Exeter, a skilled administrator, writer and antiquarian.

As far back as 1265 this area was known as Southernhay, which means the southern enclosure or southern field. In 1667 part of the grassy open space was set aside for public gardens, some of the first in the country, footpaths were laid and elm trees planted. But cattle continued to graze in the surrounding fields until the late eighteenth century.

From 1278 until 1830 Southernhay was also the site of the Lammas fair where the citizen’s of Exeter gathered to enjoy the delights of the traders’ stalls and entertainments. But those who gathered in Southernhay on the morning of 15 August 1557 were likely not in holiday mood. They had come to witness a poor Cornish woman meet her end in the flames as Exeter’s only Protestant Martyr during the reign of Queen Mary.

Agnes was born around 1503 in Cornwall but in her youth she worked in Exeter as a domestic servant. It may have been during those early years in the city that she first heard and saw things that would change her life. She may even have been in the crowd when, on 15 January 1531, a protestant was martyred for his beliefs.

Thomas Benet, a Cambridge born and educated man, became increasingly disillusioned with the ways of religion that had held sway in England for generations. He moved to Devon so that he could exercise his religious conscience more freely in a county where no one knew him. After spending some time in Torrington in 1524 he moved to Butcher’s Row in Exeter where he took up teaching and studied the scriptures. A few years later Benet felt he could no longer tolerate what he considered were the religious abuses of the time. He protested by putting up posters saying things like “we ought to worship God only, and no saints.” When he sent his son out next morning to put up more posters the boy was caught and Benet apprehended. Charged with heresy he was interrogated and, it is said, kept in stocks and irons at the Bishop’s Palace while he was pressured to recant. Benet refused to do so and was eventually burned at the stake at Livery Dole, Heavitree, a parish just outside the city walls. If that young woman, Agnes, did indeed witness Thomas Benet’s execution, perhaps that is what prompted her to begin to question the teachings of the clergy.

However that may be, Agnes returned to Cornwall where she married a Launceston man named Prest, who was an ardent follower of the old ways. Agnes was said to be cheerful, patient, and sober and she worked hard with her husband to make a living at spinning in Northcott Hamlet, near the village of Boyton and attended church with her neighbours. When, under Edward VI, Latin was no longer used in church Agnes must have listened hard. Although she was uneducated was soon said to know the Bible almost by heart. She found herself firmly on the opposite side of the religious divide from her husband. The historical record does not tell us if Agnes’ husband made an outward show of accepting reform during Edward’s reign but their children were brought up in the traditional way and were reported to be much addicted to the superstitious sect of Popery. But Agnes’ conscience would not allow her to accept the reversal of reform enforced after Mary Tudor came to the throne in 1554.

It seems that Agnes and her husband tried hard to convert each other. She is reported as saying, “When I would have him to leave idolatry and to worship God in Heaven, he would not hear me, but he with his children rebuked and troubled me.” Prest tried to compel his wife to go to Mass, make her confession and follow the Cross in procession, but Agnes refused to do any of these things. Finally she fled. According to John Hooker, “Her own husband and children were her greatest persecutors, from whom she fled, for that they would force her to be present at Mass”.

Agnes left home and tried to support herself by spinning. Perhaps she missed her family or perhaps she simply could not make ends meet, for after a while she returned home. She got a hostile reception from her husband, family and friends. They led her to the parish priest and accused her of heresy. Agnes was arrested and spent several months in the Launceston jail before she was brought to Exeter to be interrogated by Bishop Turberville.

Under questioning Agnes was reluctant to accept belief in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The bishop gave her a month's parole and she became a servant, working again at spinning and carding, in the home of the keeper of the Bishop's prison. Her husband was sent for, but she refused to go back to Cornwall with him, saying, he was not only an idolator himself, but allowed her to have no peace because she was not one also. She was continually approached by the clergy who sought to make her change her mind. But Agnes stood firm in her beliefs and continued to decry idolatry. After she challenged a Dutch stonemason repairing images of saints in Exeter Cathedral with the words: “What a madde man art thou to make them new noses, which within a few dayes shall all lose theyr heades,” she was sent back to prison.

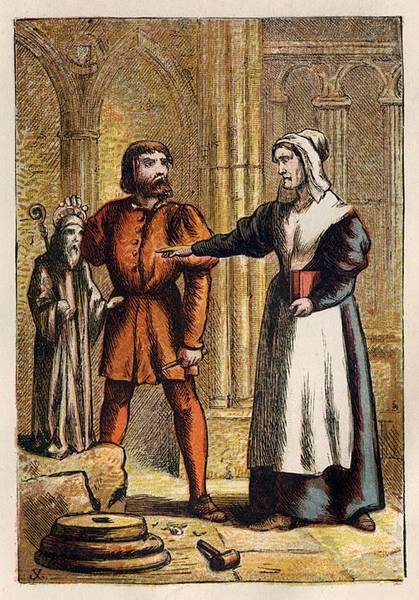

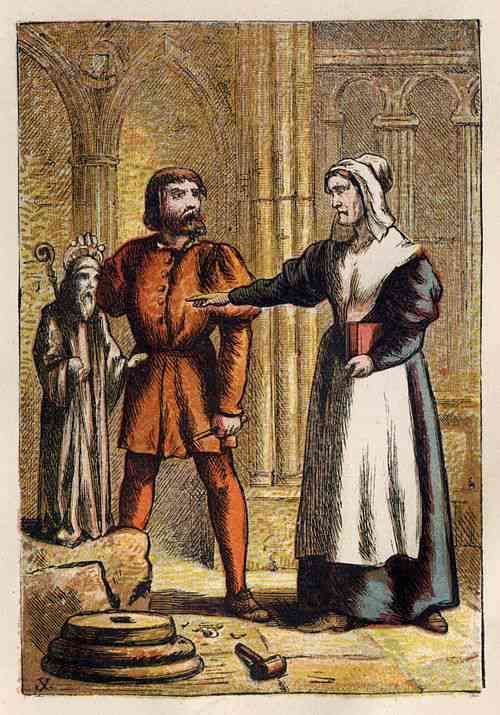

This illustration by Kronheim from the 1887 edition of Foxe's Book if Martyrs depicts Agnes and the stonemason (sourved via Wikimedai Commons)

Agnes was tried before John Petre, Mayor of Exeter, in the Guildhall in the presence of the bishop. The charge against her was heresy, chiefly against the Sacrament of the Altar and for speaking against Idols. She still refused to give up her convictions. Found guilty and sentenced to death by burning she was moved to the City goal beneath Rougemount Castle.

Theruins of rougemouth Castle, Exeter

Having refused one last chance to recant, on 15 August she was led outside the city walls to Southernhay by the Sheriff and city officials to be burned at the stake. No one knows the exact spot.

Agnes was not the only woman to suffer that gruesome fate in Southernhay. John Hooker tells us that in 1571, Agnes Jones was "burnt to death in Southernhay for poisoning her husband.” But Agnes Prest is the only one known to have to died there for her beliefs.

It seems that the western side of Southernhay kept its reputation as the Burning Place for many years since John Cole's map of 1709 still refers to it as such.

In 1909 a memorial was erected in Denmark Road, Exeter, to Agnes and Thomas Benet, known as the Exeter Martyrs. Designed by Harry Hems and erected with money raised through public subscription, it bears two bronze sculpted relief panels depicting Agnes burning at the stake and Thomas Benet nailing his protest to the door of the Cathedral.

The bronze plaques on the memorial

The version of Agnes’ story in the second edition of Foxes Book of Martyrs published in 1570 describes how Katherine Raleigh — a woman of noble wit and godly ways — visited the Cornish woman in her prison cell. Foxe says that Katherine returned to her home at Hayes Barton near East Buddleigh very much impressed and moved by the martyr’s deeply held faith. It does not seem too far a stretch to imagine that hearing his mother speaking of Agnes and her cruel death made an equally strong impression on her youngest son. That in its turn may well have influenced Sir Walter Raleigh’s lifelong hatred of catholicism.

That description of Katherine in Foxe’s book of Martyrs gave me the title for my novel of her life “A Woman of Noble Wit”.

If you've enjyed this post do share on your social medai using the buttons below