Riding and Riding Apparel for women in Tudor and Elizabethan England

— a post prompted by watching the Starz TV series Becoming Elizabeth

August 2022 brought quite a heatwave to Devon. It was far too hot to work in my attic-room office, so I took some time off to binge-watch the Starz TV series Becoming Elizabeth. Set in the years immediately following the death of King Henry VIII, it concentrates on the relationship between the young princess Elizabeth and the charismatic but dangerous Thomas Seymour. I often find TV dramatisations disappointing but, despite having a few qualms about some of the plot lines, I rather enjoyed this one.

The locations are brilliant and details like candlelit rooms and the ever present but totally ignored serving people evoke a real feeling of what life was like in wealthy households in Tudor England.

Costumes can sometimes let down otherwise well-crafted dramatisations, but in this series they are rather good, especially where clothing from well known portraits has been so faithfully reproduced as shown here.

But there was one aspect that had me reaching for my copy of Janet Arnold’s “Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlocked”. Mary Tudor and her half sister Elizabeth were shown riding astride wearing tightly fitting breeches that looked more like leggings beneath gowns with a skirt split to the waist at the front.

Riding astride

I was not surprised to see the princesses riding astride. There’s a good deal of evidence that women have done so throughout the ages.

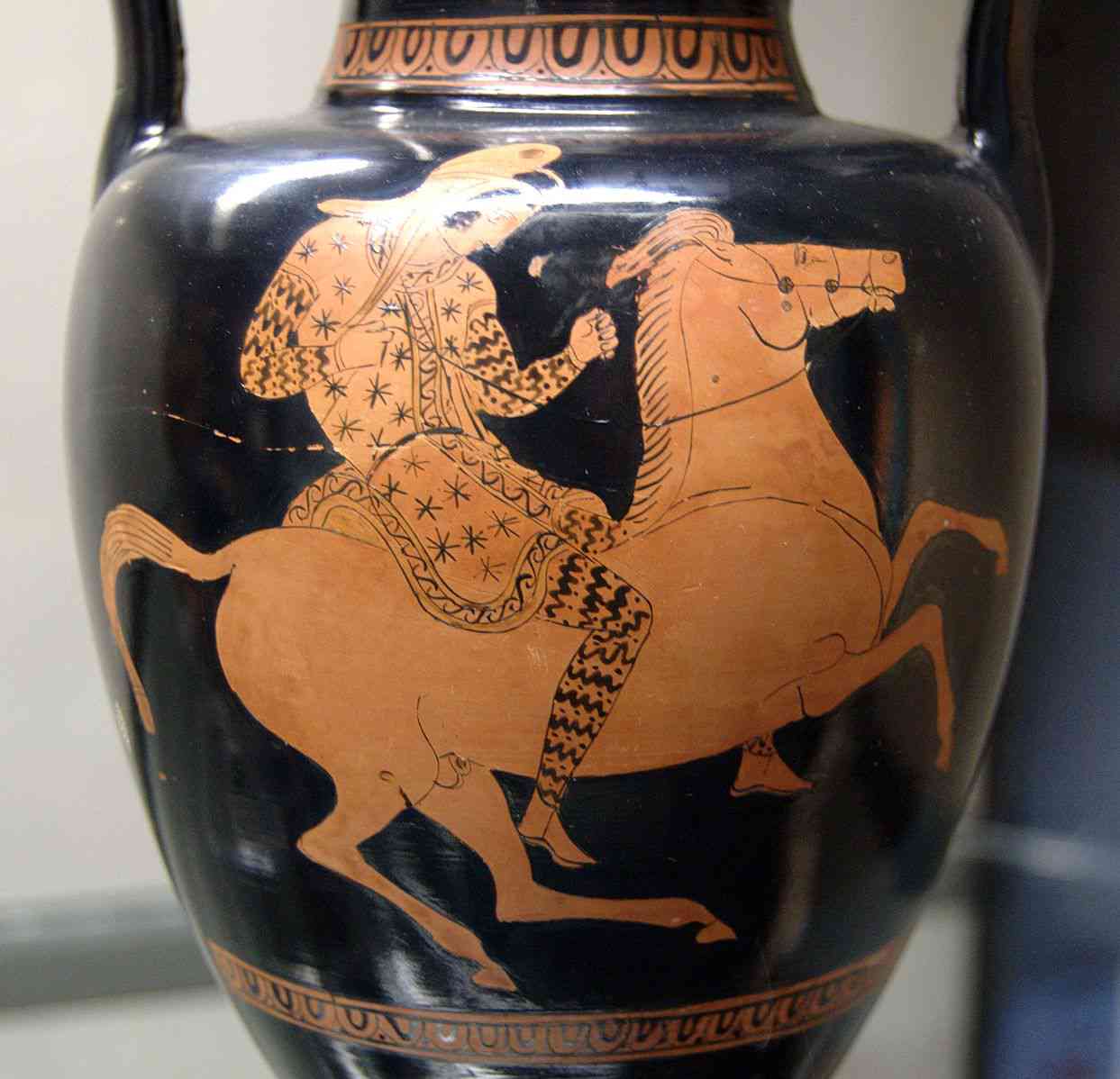

Trouser-wearing Amazon’s, the warrior women of the Eurasian Steppes, are supposed to have ridden astride as depicted on this vase.

In the eighth century Tang dynasty female polo players did so, as shown in the wonderful sculpture on the right.

Charlemagne’s six daughters are recorded as riding astride whilst hunting, and in the Ellesmere Manuscript (held by the Huntington Library in San Marino, California) Chaucer’s Wife of Bath appears to be riding with a leg on each side and wearing two spurs.

But long skirts made riding astride quite impractical. It was also seen as immodest. When in 1382 Anne of Bohemia rode side-saddle across Europe to meet King Richard II, the idea that it was indecent and vulgar for a woman to ride astride really took hold. So women usually rode as a passenger sitting behind a man, clinging to his waist, or on a padded cushion or pillion.

In the late fourteenth century a new sort of side-saddle was designed — a chair-like construction, where the woman sat facing sideways with her feet on a footrest. But it was not until the sixteenth century that a woman could ride side-saddle with real control over her mount.

It is Catherine de Medici who is said to have developed a more practical design of side-saddle. Rather than keeping both feet placed side by side on the footrest, she hooked her right leg over a single pommel. It’s been suggest that this meant she could show off her shapely ankle and calf to their best advantage. But more importantly it allowed her to face forwards and gave her much more control over the horse. This arrangement even allowed the rider to trot and canter safely. Although there were some adjustments to the side-saddle over time, it was not until the 1830s when a second pommel was added that women could really stay on at a gallop and jump fences with safety whilst still conforming to the expected standards of modesty.

It is not known for certain when this style of side-saddle was first adopted in England. An emerald green velvet saddle cloth, edged with gold fringe and tasselling, said to have been used when Elizabeth visited Bristol in 1574 came up for sale in 2012. It seems to be a simple cloth with a padded pommel for riding side-saddle.

In my novel A Woman of Noble Wit I have a young Katherine riding astride. One of the few items mentioned in Katherine Raleighs will, made just before she died in1594, was her saddle cloth. I wonder if it looked like the one above.

Riding Apparel

Always in the public eye and keen to present her dazzling image Queen Elizabeth liked to appear on horseback, since it meant she could be seen over the heads in a crowd. She wore stunningly beautiful gowns when travelling and no doubt she was splendidly attired when she visited Bristol using the saddle cloth mentioned above.

In these two woodcuts from The Noble Art of Venerie by George Turberville, 1575 (British Library) she appears to be wearing clothes similar to her usual magnificent day wear.

Queen Elizabeth did possess some garments made specifically for riding. In her book which details inventories of the royal wardrobe, Janet Arnold lists riding hoods made of silk, black taffeta and velvet, which would have kept her hair tidy. She tells us that one Walter Fyshe made a “round ryding kyrtle of blac pynked velvet with bodies of the same and a gard and weltes of blac velvet lined with blac taffeta.” This would have been worn under a gown. (The gard and welts were added strips of material applied at the hem, also used as binding to stop fabric from fraying. In this case they may also have added length the kirtle to cover her legs while riding.) Only one riding gown appears in the inventories, altered and enlarged by he same master Fyshe in 1568. A new lining was also added and replaced only a year later, suggesting that the gown had a lot of wear. The skirt would have been made long enough to cover the feet when she was seated side-saddle. A ryding cloak is also mentioned as having fur removed and having a new lining added.

There is also mention of a riding coat, probably some kind of loose coat or cassock, and safeguards — an outer skirt or petticoat that fastened at the waist over the gown and probably tied to the stirrups with strings, which would prevent the skirt from flying up. This arrangement also protected the skirts from dirt, but must have been quite dangerous with potential to drag the rider along if unseated. Safeguards are listed as part of a set with cloaks and jupes — coarse long jackets, possibly like a shepherds smock — made from a tough fabric like gaberdine. Cloth hose and knitted stockings may have been worn when riding for extra warmth.This all suggests that normal day wear was being protected by extra layers when riding, but there is no mention of anything we might recognise as breeches.

Breeches, hose or braies

I found this definition for breeches — a man's bifurcated outer garment, covering the lower body from waist to knees or just below the knees. I have searched the records in vain for any definite indication that Elizabeth owned any garments that would fit that description. Janet Arnold does include one mention — Queen Elizabeth presented a pair of gaskins, or gallygaskins (a type of breeches so called because first warn by the gascons) to William Shenton, the fool, in 1575.

Men sometimes wore an early form of linen underpants known as braies or drawers but these were not generally adopted by women until the nineteenth century. It has been suggested that sixteenth century women like Catherine de Medici may have worn something similar beneath their skirts when riding for modesty, but I have yet to find any evidence of it.

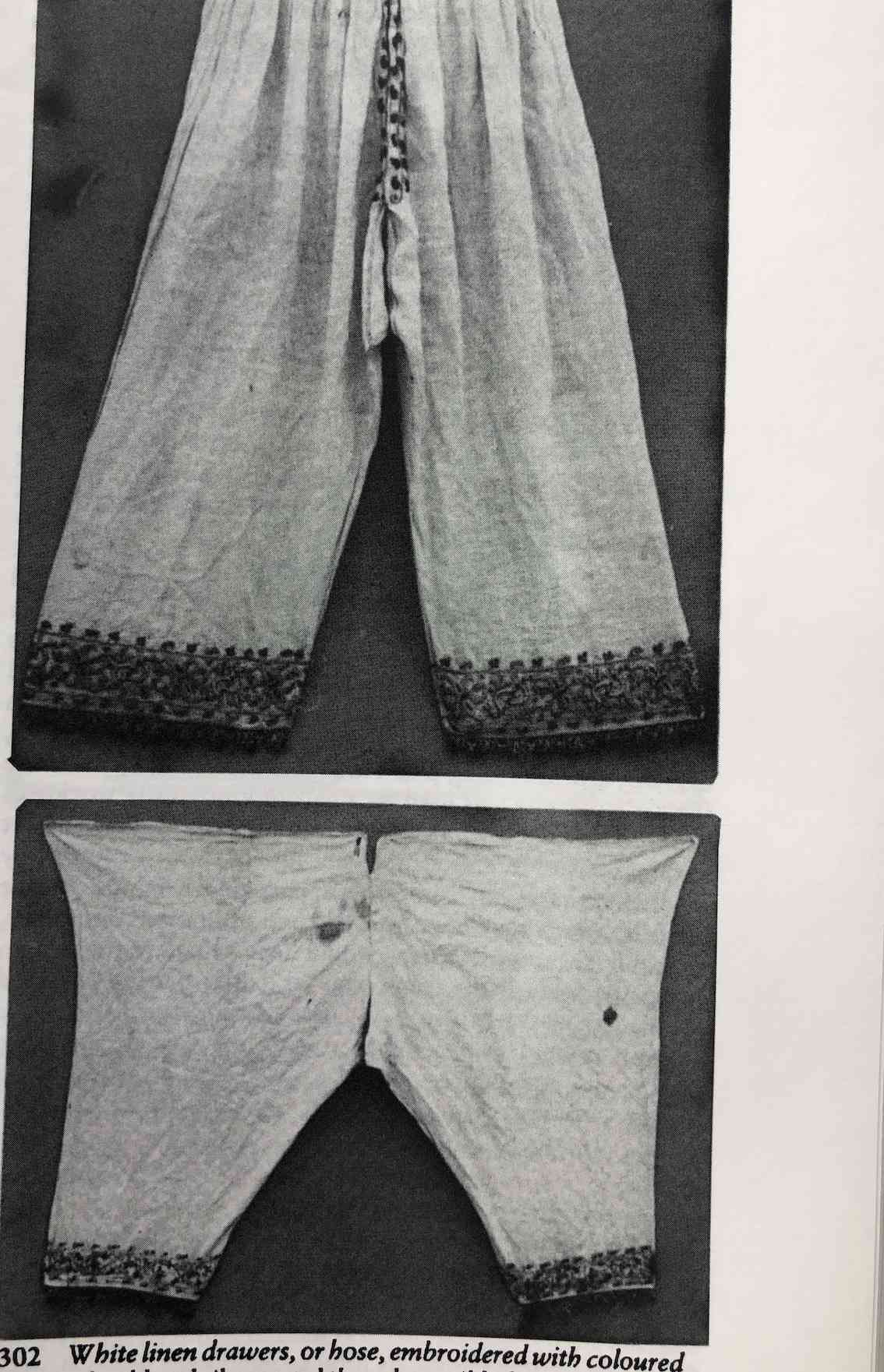

These two pairs of drawers in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, are thought to be Italian and to date from the sixteenth century but it is not known if they were worn by a woman or a man.

The only items listed in the wardrobe inventories that could possibly be such linen drawers are the double linen hose mentioned in 1571 and 1587, but these may equally have been leg coverings for wear beneath expensive knitted stockings.

There is one pair of drawers definitely associated with Elizabeth, however. During restoration of her funeral effigy in 1995 it was found that the original corset and drawers from 1603 still survived.

It’s worth mentioning that In the sixteenth century men’s hose came in two parts. The upper part might be considered as a form of breeches, worn over a lower part more like tight-fitting elongated stockings that were fixed to the doublet at the waist by laces known as points. In the early sixteenth the upper part of men’s hose was generally voluminous or, at least, very loose fitting. Venetian breeches became more popular for men in the late Elizabethan and early Stuart period. They were still very full and gathered at the top but tapered steeply to an unconfined knee held closed with lacing holes and ribbon. This does not sound quite like the garments worn by the princesses in the film, and I doubt they’d have worn thigh high boots either.

Mary Queen of Scots

I understand that John Guy states in his biography of Mary Stuart that Mary took up hunting and adopted the "daring fashion of wearing breeches in florentine serge underneath her skirts”. (I haven’t read this so don’t know if he gives a source.) There is apparently a reference in the sixteenth century document the "Diurnal of Occurrents" to Mary and Darnley banqueting with the French ambassador which reads

"the Queenis grace and all her Maries and ladies were all cled in men's apperell…"

She is also said to have been disguised as a page when she escaped from Borthwick Castle. But does that necessarily mean she wore what we would recognise as breeches?

Conclusion

So my conclusion is that Mary Tudor and her sister Elizabeth almost certainly rode astride at the time depicted in Becoming Elizabeth, but its unlikely that they wore tight-fitting breeches under split-front riding gowns quite like the ones shown. Dressed like that they seemed to have more freedom, more agency than women, even royal women, likely had in those times. Perhaps that was the intention and perhaps it helped the story telling. I think it’s really quite hard for us, with our modern day view of the world, to imagine how even powerful, strong women, would have accepted the restrictive social norms of their time. They would probably have kept their legs covered. But whether the clothing was strictly accurate or not it certainly didn’t stop me thoroughly enjoying this thought-provoking series.

What do you think?

If you've enjoyed this post pelae share on social media using the links belowe