Missing Persons — Who were the Typical Tudors?

Missing Persons — Who were the Typical Tudors?

Tudor Tailor Conference, Nottingham, 22-25 October 2022

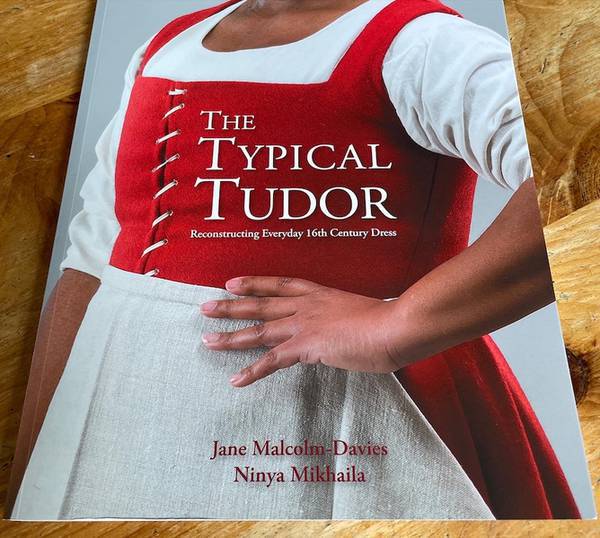

They say the best things are worth waiting for. Well, the conference to launch the Tudor Tailor’s new book “The Typical Tudor” was certainly worth the wait. After several false starts because of the pandemic, Tudor costume enthusiasts from all over the world gathered in Nottingham on a rather wet weekend. What a treat was in store for us.

on a rather wet weekend. What a treat was in store for us.

We were greeted with a glass at registration on Saturday afternoon and there was time to check out some of the reconstructed garments at the Missing Persons exhibition.

An early start on Sunday morning saw us all struggling through torrential rain to the National Justice Museum. Greetings were exchanged as we squeezed onto the polished wood benches in the imposing restored Victorian Civil Courtroom. Some of us were meeting old friends, others were making new ones. The buzz of conversation grew ever louder until a respectful hush descended as we were called to order. The air crackled with excitement as we rose to allow the judge, resplendent in wig and gown, to take his place with due pomp.

Retired circuit judge Andrew Hamilton was to preside over a courtroom drama that would test the evidence to the limits. On trial — evidence for those missing people; the ones whose footprint on the historical record is light, the ones who lived in the shadows; the lost souls of Tudor History.

The question — who were those Typical Tudors and what did they wear?

Counsel for the defence Ninya Mikhaila called a series of expert witnesses to testify to the evidence for what those typical tudors wore. They were cross-examined by Ninya’s learned friend the counsel for the prosecution, Dr Jane Malcolm-Davies. The line of questioning was probing and forensic.

It was clear from the outset that the Judge would take some convincing. He was quite prepared to ask questions of his own if he thought it would assist the jury of twelve specially selected members of the audience to reach their verdict.

The first expert witness to plead her case was Dr Tarnya Cooper, Curatorial and Collections Director for the National Trust and author of Citizen Portrait: Portrait Painting and the Urban Elite of Tudor and Jacobean England. She maintained that it was not only the nobility who had their portraits painted. Clergymen, doctors, dancers and musicians, merchants, goldsmiths, silversmiths, and skinners all had their likeness taken to hang on their parlour walls. However, only 40 percent of such portraits, which were often painted on wooden panels, survive. On the other hand, the portraits of these people tended to be more lifelike, contrasting with the highly stylised images of royalty. Portraits often revealed the type and quality of cloth, the importance and character of the sitter, the style of dress worn, but also showed people in their very best clothes.

I was left thinking that portraits were useful but gave an incomplete picture of the full range of what everyday people wore. While I was surprised to find that some of the “middling sort” could afford to have their likenesses taken, it occurred to me that not many people, whatever their status, would have chosen to be painted in their underwear. Portraits did not tell us what they wore beneath the fine fabrics and all those woollen gowns and doublets.

The next witness was Dr Alex Hildred, Head of Research and Curator of Ordnance and Human Remains at the Mary Rose Trust and author of Mary Rose: Her story, Their Story, Our Story, History. Dr Hildred gave details of finds brought to the surface from King Henry’s ship the Mary Rose that went down in 1545. A wealth of ordinary objects, nit-combs, wine flasks, pewter dishes, spoons, a pomander and cord, ear scoops, wooden bowls, and quantities of weapons — bows, arrows etc, have survived to give a unique picture of what life was like on board. Most belonged to the ordinary sailors and bowmen who were crammed into the ship. But there are just few items that might have belonged to the officers such as high-quality sword belts. (Katherine Raleigh’s cousin Sir George Carew was one of the officers lost.) Little clothing survived but some leather jerkins and a collection of shoes have been studied.

While the Mary Rose remains are invaluable as a time capsule of life on board, not much clothing or fabric has actually survived being immersed in salt water for so long, and what has been recovered all belonged to men.

Pat Poppy, an Independent Scholar and early modern clothing blogger was the next witness and gave evidence gleaned from a wealth of written records she has studied, including household accounts, wills and inventories. Various garments are named and described frequently, such as the smock (which later papers in the records describe as a shift, even later as a chemise) and the kirtle. Fewer colours were recorded in the wills of ordinary people but red petticoats were common. Descriptions of fabrics and yarns help build the picture.

I was impressed by the volume reliable evidence that could be extracted from documents of this nature, although, of course, the poorest people rarely left wills themselves. But they were recorded in the bequests of better-off people who often left clothing specifically for the poor which sometimes specified fabrics and yardages.

Susan North, Curator of Fashion at the V&A Museum and author of Sweet and Clean? Bodies and Clothes in Early Modern England, was the next witness. She emphasised that clothing was expensive, often passed on or re-purposed and that it was biodegradable, so few items actually survive from the period. Most people wore second hand clothes — for example, serving people received clothes as perks from their masters and mistresses. There was an industry recycling clothing; paper was made from linen and old fabrics; woollen rags were used as manure. The few items of historical dress that do survive are here because they have been victims of poor housekeeping or “benign neglect”. They are things that been overlooked and forgotten, hidden away in a chest or a drawer, for generations.

Susan was then given a mystery object, something she had never before seen, to analyse. To my delight, it turned out to be a farthingale sleeve support, recently discovered by The Tudor Tailor. (Read more about this extraordinary survival in my other blog article: Rare survivors: Farthingale sleeve supports.) It was fascinating to learn of the process Susan follows to assess unknown items which are often presented to the V&A collection. She checked the quality of the fabric, the structure of the garment, the state of repair and preservation in an orderly manner before coming up with an accurate assessment of what this item was.

Dr Maria Haywood, Professor of Early Modern History at the University of Southampton and author of Dress at the Court of Henry VIII gave her evidence via video. She explained the operation of the sumptuary laws (the name comes from the Latin word “sumptus” meaning cost or expense) which were in force in many countries including Italy, Scandinavia and Japan. Such laws attempting to control spending on clothing and other luxury items such as foods have been in use throughout the ages, from ancient Greece and Rome right up to the nineteenth century. In Scotland, England and Wales, Acts of Apparel initially focused mainly on the dress of men, while it was necessary to “read between the lines” to divine what was allowed for women. Most colours were unregulated but purple and scarlet are mentioned specifically. Although the middling and poorer classes had a wider range of less drab colours than might be expected, expensive imported and expensively dyed fabric was restricted.

Kathy Davies, Visiting fellow at Kellogg College, Oxford and author of Artisan Art and Wall Paintings in the Welsh Marches 1550 to 1650 was unable to give her paper as she unfortunately had covid. Ninya and Jane discussed some of her images of domestic wall paintings – many in private houses and therefore little known - which provide a wealth of information on clothing.

I found this visual evidence particularly convincing — the images on the interior walls of people’s homes looked like real people.

The final witness, via video, was Hilary Davidson, Chair of the masters in Fashion and Textile Studies, History, Theory, Museum Practice at the Fashion Institute of Technology New York and author of Dress in the Age of Jane Austen: Regency Fashion. Hilary suggested that the three sources of evidence – pictorial, artefactual and documentary come together to help us understand clothing in three-dimensions. Her proposal, which she characterised as a milking stool with three legs, drew on The Tudor Tailor’s foundation for reconstructions – the PAD – and suggested that judicious use of all three sources produces a reconstruction which is greater than the sum of its parts.

The Judge summed up the case, the Jury retired and soon returned to give their verdict. After what was reported as heated debate, they announced “Case proven!” but also emphasised the importance of continuing research and study as new evidence of all kinds comes to light.

We had all enjoyed a lively and innovative presentation that kept us engaged, and presented some of the fascinating evidence that underpins the new book The Typical Tudor. Throughout the proceedings, a series of “ghosts” in Tudor dress appeared in the gallery, and we were able to examine their reconstructed garments more closely at the evening event and the exhibition on the next day.

Gala evening

But Sunday was not over. Later, we donned our glad rags and braved more near biblical rain to visit Holme Pierrepont Hall, an atmospheric Tudor manor house dating back to about 1500, for a celebratory reception. The highlight was Amber Butchart's fascinating account of her work using forensic analysis of clothing to help solve crimes. Dress historian Amber will be familiar to many from her work on the BBC4 series A Stitch in Time and her contributions to the BBC’s Great British Sewing Bee.

Monday’s activities

On Monday, a series of events had been arranged for us, starting with a tour of Nottingham's Lace Market area with our irrepressible guide, Ezekiel Bone. In a tour specially developed for The Tudor Tailor conference we learned how the city had changed with the advent of huge and opulent lace-making warehouses and factories as the mechanisation of lace making took off.

A tour of Nottingham's caves followed. The city has the UK's largest network of caves — more than 800 are hidden beneath its streets - and we discovered how they have been used throughout history for a variety of purposes - from a medieval tannery to a smugglers’ hideout, from a meeting place for Luddite protestors to a WWII air raid shelter.

Next was a visit to a lacemaker’s workshop to learn about his family history of lacemaking and to examine examples of lace from the archives, with the chance to buy some too.

The day was completed with time to study the original farthingale sleeves (see my other blog post) and to explore The Tudor Tailor’s exhibition of garments made for the new book.

Tuesday at the Framework Knitters Museum

On Tuesday morning, an extra tour had been arranged to the Framework Knitters Museum in Ruddington, a unique surviving example of a 19th century framework knitters 'yard. We saw how framework knitters and their families lived and worked here in Victorian times, and how framework knitting gave birth to the Nottingham lace industry.

I had to leave early due to another commitment but will definitely return to find out more.

Conclusion

I cannot thank Jane and Ninya and everyone at The Tudor Tailor who worked so hard to bring us together for this truly wonderful conference to launch their new book. The best things in really are life are worth waiting for!

I thoroughly recommend the new book, The Typical Tudor. It is full of fascinating research findings and detailed information as well as new knitting and sewing patterns. If only I had more time so that I can get started on some new projects.

Preordered copies are going out now and the book will be available to buy from the Tudor Tailor’s Etsy shop from Friday 9 December 2022. Visit: https://www.etsy.com/uk/shop/TheTudorTailor

For more news from The Tudor Tailor, visit the website at https://www.tudortailor.com/

Or, better still, subscribe to Jane and Ninya’s newsletter at:

https://tudortailor.us3.list-manage.com/subscribe?u=f213c3f8181efa60e85ff0e94&id=e59a21dc69

All photos taken during the Missing Persons: Who were the Typical Tudors? conference