Rare survivors: Farthingale sleeves and supports

Farthingale sleeves — a chance to examine some very rare survivors

In an episode of the BBC’s Antiques Road Show that first aired on 30 October 2022, an incredible cache of Elizabethan textiles was presented for assessment at Wollaton Hall in Nottingham. This very rare collection belonged to the Willoughby family of Wollaton Hall, which was built in 1588 by wealthy coal baron Sir Francis Willoughby.

The items included a wonderful 500-year-old bedspread and pillowcases, but they were eclipsed by the "extremely rare" ivory silk satin sleeve and sleeve support found in the same chest.

Until this remarkable discovery, no examples of such sleeve supports were known to exist. It had been thought that the exceptionally full sleeves worn in the late sixteenth century were padded out with cloth, wire or whalebone or other stuffing materials but their precise construction as a series of concentric hoops was not previously known.

Until this remarkable discovery, no examples of such sleeve supports were known to exist. It had been thought that the exceptionally full sleeves worn in the late sixteenth century were padded out with cloth, wire or whalebone or other stuffing materials but their precise construction as a series of concentric hoops was not previously known.

In an earlier blog post, I explained how I had been one of the pattern testers who made a reconstruction of these extraordinary sleeve supports. Imagine my excitement when, at The Tudor Tailor conference to launch their new book “The Typical Tudor” (which includes patterns to recreate farthingale sleeve supports), I was able to see the originals up close.

The silk outer sleeves are stamped with a design of pomegranates and flowers which would have been created by applying a heated metal stamp to the fabric. They are also slashed.

A separate hooped support was also found inserted into the facing of the silk satin sleeve head.

The sleeve support that goes the full length of the sleeve is made from a thick cotton mix fabric called fustian, stitched with 14 casings of linen each containing a hoop of baleen, also known as whalebone — the black substance just showing in between the linen strips where the stitches have pulled away a little.

It is not actually bone but is made from a protein substance called keratin similar to that found in hair, skin, nails and horn, which lines the whale’s mouth as part of its filter-feeding apparatus. (In my reconstruction, I used split willow canes but imitation whalebone is also available from The Tudor Tailor’s Etsy shop).

This sleeve support is perhaps the earliest known use of baleen for stiffening in an extant garment. In her book Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlocked, Janet Arnold explains that although there are references to whalebone being used to stiffen farthingales for Mary Queen of Scots as early as 1562, it is not mentioned in Queen Elizabeth’s wardrobe accounts until 1580. The whalebone used in these sleeve supports is relatively thick, suggesting that techniques for cutting and using it were not well advanced at the time of its making.

As voyages of exploration (such as the one undertaken by Katherine Raleigh’s second son, Sir Humphrey Gilbert in 1583) and fishing in waters around Newfoundland and the Arctic increased, a whaling industry developed. Sarah Bendall has studied the use of baleen in women’s garments and in her book Shaping Femininity she explains that although the Muscovy company was granted a twenty year monopoly on the importation of whale products in 1577 whaling did not become an important business venture until the seventeenth century. So, at the time these sleeve supports were made, baleen was probably still relatively rare and methods of cutting and using it were still being developed.

It is not known where these sleeves and supports were made. Queen Elizabeth had specialist tailors who supplied the Royal Wardrobe with farthingales, bodies and farthingale sleeve supports. Beyond the Queen’s farthingale makers, as the fashion for stiffened bodies and farthingales spread, by the early seventeenth century other specialist tailors were established in London. Depending on the exact date of construction, the newly discovered sleeve supports may have been made either by a specialist or by a general tailor. Tailors employed journeymen and apprentices, mainly men, to do most of the stitching.

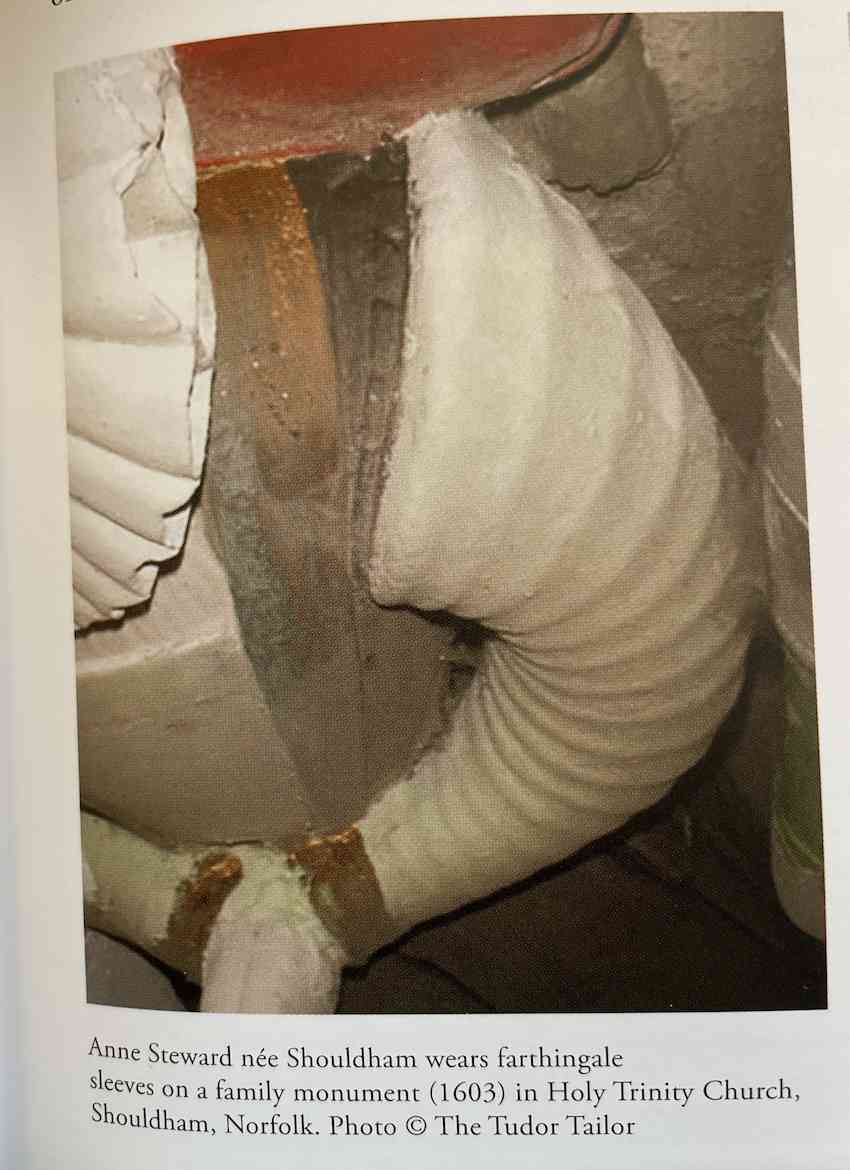

I know from my own experience that many hours of work are needed to create these garments, with considerable precision in the cutting and fitting of the hoops, and some tricky sewing to encase them in linen strips and fix them in place. The Tudor Tailor team has found evidence for the use of sleeve supports like these by people of the middling sort. This (copyrighted) photo is taken from The Typical Tudor book (with permission). It shows a church monument in a Norfolk church. This suggests that they were affordable. The fabrics and materials used were not particularly costly, even the whalebone, and it seems the extensive labour involved in production was not particularly highly valued.

I have yet to complete the oversleeves that will allow my reconstructed sleeve supports to see action as part of a late 1590s gown. From trying on my reconstructions, however, I can report that they are much more flexible that I expected and allow quite a range of movement.

The fashion for huge sleeves developed alongside the large wheel or French farthingales — perhaps such large arms were intended to emphasise or balance a slender waist above the wide skirts. Janet Arnold suggests that the desired sleeve shape might first have been provided by additional layers of sleeve linings being worn on top of each other. (There are records of large numbers of holland sleeves with ribbons being provided [48 pairs in 1588] in the Royal Wardrobe Accounts.) When the extra layers proved insufficient, the records suggest that farthingale sleeve supports were used more frequently.

Portrait of an unknown Elizabethan lady, traditionally thought to be Elizabeth Throckmorten (later the wife of Katherine Raleigh's son, Sir Walter Raleigh). Circle of Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger - Wikimedia commons.

I feel enormously privileged to have been able to study these incredibly rare survivors. My thanks are due to Jane and Ninya, The Tudor Tailor, for making this possible.

All photographs except the whalebone and the portrait (both from Wikimedia Commons) were taken by me at the Missing Persons: Who were the Typical Tudors? conference in Nottingham, 22- 25 October 2022. They are not to be used for publication without written permission from The Tudor Tailor.

References:

Queen Elizabeth’s Wardrobe Unlocked by Janet Arnold

Shaping Femininity by Sarah A Bendall

The Typical Tudor by Jane Malcolm Davies and Ninya Mikhaila