Did Henry VIII eat turkey for Christmas dinner?

Did Henry VIII eat turkey for Christmas dinner?

It’s a question that often comes up at my Tudor Christmas events. So here’s a bit about the history of our favourite Christmas dish and a few personal memories of the noble turkey bird.

A Christmas feast at the court of King Henry VIII must have been a truly magnificent spectacle. Every type of meat, fish and fowl you can imagine — including some that seem very strange to us today — found its way on to the groaning tables at Greenwich Palace and Hampton Court. But was our Christmas favourite, the turkey, served up alongside the peacocks and swans all dressed in their feathers, the herons and storks, the woodcock and snipe and other birds that jostled for position beside the traditional boars head, roasted venison and beef?

The answer is: in the later years of his reign — definitely yes. By the fifteen forties we can be fairly certain that a well dressed turkey cock would have been amongst the dishes served to the huge crowds, sometimes as many as one thousand people, who attended the mid-winter festivities at court.

(Tthis photo was taken at NT Cotehele December 2022 - no swans or other fowl, but a rather fine boar's head.)

When the Spanish  arrived in the Americas the native wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) soon came to their notice. They described it as “a kind of peacock with great hanging chins”. Turkeys had been domesticated in Mexico since possibly as early as 800 BCE and by the fifteenth century the Aztecs were raising and eating tens of thousands of them. A large bird, easily domesticated, which provides succulent tasty meat and could be dressed for table dramatically with tail feathers intact, it’s no wonder that the turkey presented an attractive proposition for Spanish traders. In the early 1500s they began to bring birds that had been domesticated by indigenous Americans to Europe and Asia. Soon most Spanish ships leaving the Americas carried a few breeding pairs.

arrived in the Americas the native wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) soon came to their notice. They described it as “a kind of peacock with great hanging chins”. Turkeys had been domesticated in Mexico since possibly as early as 800 BCE and by the fifteenth century the Aztecs were raising and eating tens of thousands of them. A large bird, easily domesticated, which provides succulent tasty meat and could be dressed for table dramatically with tail feathers intact, it’s no wonder that the turkey presented an attractive proposition for Spanish traders. In the early 1500s they began to bring birds that had been domesticated by indigenous Americans to Europe and Asia. Soon most Spanish ships leaving the Americas carried a few breeding pairs.

There is some debate about when turkeys first appeared in England. It’s often claimed that a navigator called William Strickland imported six wild turkeys in 1526 and sold them for tuppence (2d: two-old-pence) each in Bristol market. Strickland is said to have continued in the turkey trade and to have made so much money that he was able to build a stately home in Boynton, near Bridlington, East Yorkshire. In 1550 Strickland was granted a coat of arms that featured “a Turkeycocke in his pride proper”.

The photo shows the Strickland Family Crest, a turkey, at St Mary's Church, Deerhurst, Gloucestershire beneath a stained glass window situated in the north aisle that commemorates Hugh Strickland (1811–1853), a well-known geologist.

Strickland and his descendants clearly felt they owed their wealth to the bird, but unfortunately the evidence doesn’t quite stack up for William. In her book “A Tudor Christmas” Alison Weir tells us that Strickland was not born until around 1530. So while there may be a record of those six turkeys being sold in Bristol, perhaps it wasn’t Strickland who sold them. Other sources, say turkeys first came to England via the Spanish Netherlands.

The Spanish named them gallinas de la tierra (local chickens) or gallopavos (chicken-peacocks). Turkeys probably got their common name because they reached European tables through shipping routes that passed through Turkey. A bird people were already familiar with, a guinea fowl that came from sub-Saharan Africa, also came to Europe via the eastern spice trade routes that passed through Turkey, and this may have caused confusion.

In France they thought the turkey came from India and called it coq d’Inde, meaning “rooster of India”. That may have been because turkeys were imported along with spices that came from India and beyond. Or it may have been due to a common misconception that India and the Americas were one and the same.

No-one seems to have thought of adopting the name used by the Native Americans — huehxolotl — as for some other “new world” imports. Perhaps it was just to difficult to pronounce, or had some other connotations. Annie Gray in her book “At Christmas we Feast” shares the interesting snippet that Avocado comes form an Aztec word also used as slang for testicles!

However they first arrived and got their name, turkey’s would soon become an exotic favourite for the English upper classes. The birds had a lot more meat on them than small Tudor chickens, meat that was much more palatable than other large birds like swan or peacock.

In 1541 the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer sought to rein in the excesses of some high-ups in the church by bringing in a sumptuary law that permitted members of the clergy just one large fowl permeal. He said

“of the greater fishes or fowles, there should be but one in a dish, as crane, swan, turkeycocke, haddocke, pyke, tench.”

Which just goes to show how popular turkey had become. So I don’t think there can be much doubt that King Henry VIII enjoyed a good turkey dinner.

From the early 1600s turkeys were mainly farmed in East Anglia where they could be fed on grain and corn that grew well on the flat, drained fen lands. Most of these turkeys were raised to be sold at Christmas time in the London markets, which were within walking distance — though it might take up to two months in some cases. But turkeys weren’t often kept in other parts of the country. They gained a reputation for being a difficult bird for the majority of smaller farmers to return a profit on and remained a Christmas treat only for those who could afford them. The turkey didn’t really become available more widely for Christmas dinner until after the second World War.

However, in the early nineteenth century one farmer in Northamptonshire was certainly rearing turkeys. On the fourteenth day of December 1822 my three times great grandfather, William Payne, placed an advertisement in the local newspaper concerning the theft of twelve turkey cocks from his farm in Gayton.

My mother revived the family tradition of raising turkeys for the Christmas trade in the 1960s. I can testify to how aggressive and crafty a large turkey cock can be. One huge bird, kept for breeding, had a particular delight in pinning me against the wall so that I had to fend him off with a broom until someone came to rescue me. December was an exhausting month as the whole family, me included, had to lend a hand to pluck and draw the birds for sale. There was always one that was too large for any customer to want. That was the one we cooked for our own Christmas meal, often after cutting off legs and parson’s nose to squeeze it into the oven. I must admit I’m not a great fan of turkey these days.

I leave you with a verse penned by Thomas Tusser in 1573

Good husband and huswife now chiefly be glad,

Things handsome to have, as they ought to be had.

They both do provide, against Christmas do come,

To welcome good neighbour, good cheer to have some.

Good bread and good drink, a good fire in the hall,

Brawn, pudding, and souse, and good mustard withal.

Beef, mutton, and pork, shred pies of the best,

Pig, veal, goose, and capon, and turkey well drest,

Cheese, apples, and nuts, jolly Carols to hear,

As then in the country, is counted good cheer.

What cost to good husband is any of this?

Good household provision only it is:

Of other the like, I do leave out a many,

That costeth the husbandman never a penny.

Merry Christmas one and all!

Rosemary Griggs December 2022

This article has been compiled using a range of well documented sources and books including:

A Tudor Christmas by Alison Weir and Siobhan Clarke;

At Christmas we Feast by Annie Gray i

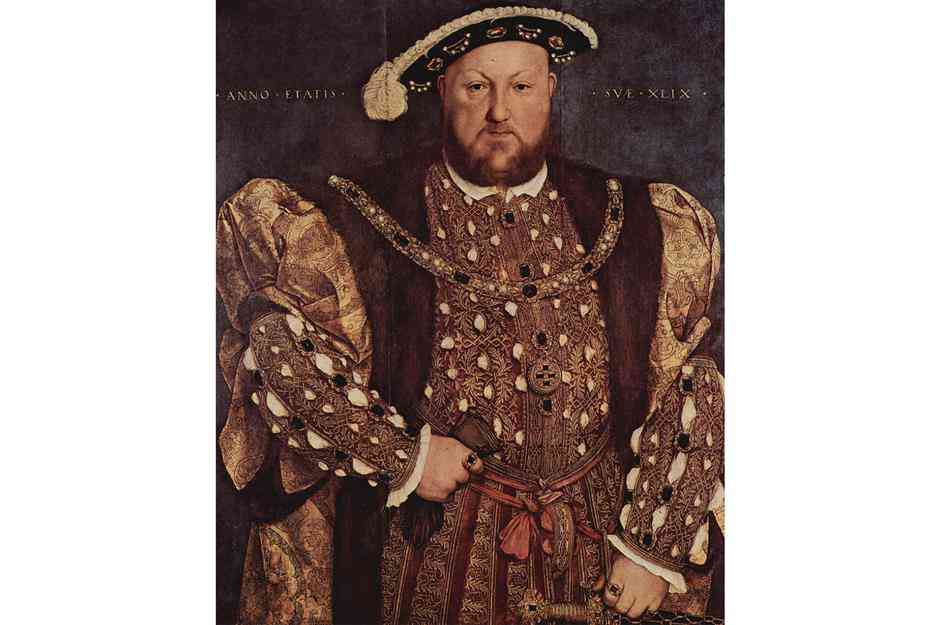

Photos of turkeys, drawing of a wild turkey by James Audubon., King Henry VIII and the Strickland family crest in St Mary's Church are all via Wikimedia commons