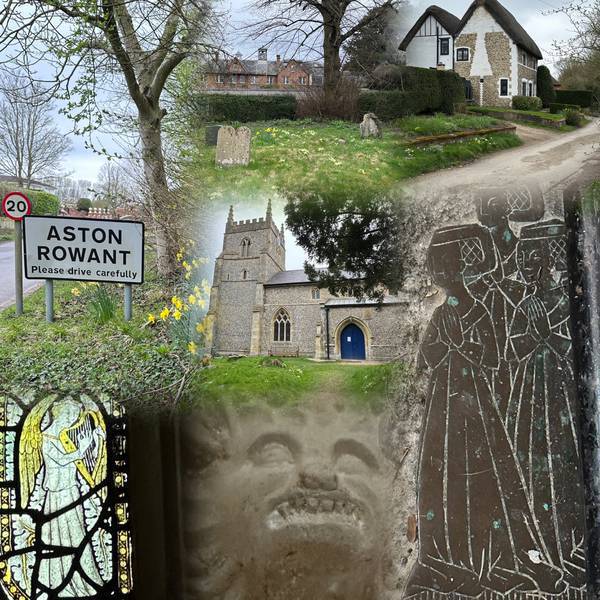

Aston Rowant, Oxfordshire: Princess Elizabeth passes by on her journey to Woodstock

Today Aston Rowant is a tranquil village with pretty thatched cottages, a village green and the charming parish church of St Peter and St Paul. The village lies on the edge of the Chiltern Hills in South Oxfordshire, just off the M40. However, in the sixteenth century, the main road from London to Oxford may have run along what is now Church Lane, next to the church.

History touched this quiet little village when, one morning in May 1554, Princess Elizabeth passed by.

The Coronation Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I. Image public domain through Creative Commons licensing, NPG, London.

Elizabeth had been held captive in the Tower of London for two months on suspicion of involvement in a rebellion against her catholic sister’s marriage to Philip of Spain. The marriage was not popular. Fears about the return of Papal authority were heightened by concerns that it would lead to Spain having an undue influence on English politics. In early 1554, these concerns led a group noblemen to plan a rebellion.

Sir Thomas Wyatt from Kent, Sir Peter Carew from Devon, Sir James Croft from Herefordshire and the Duke of Suffolk from Leicestershire aimed to depose Mary. They planned to replace her with Elizabeth, whom they intended to marry to Edward Courtenay. Edward had Plantagenet blood, being the son of Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter. He had been confined in the Tower of London since his father’s execution in 1539. When she came to the throne Queen Mary released Edward and for a while it was thought she might marry him. But instead she chose Philip of Spain.

The conspirators planned three rebellions in separate parts of the country — in the Midlands, the West Country and Kent. They thought Government forces would have to decide which rebellion to address first, stretching their resources. Local victories might then draw in more and more supporters among the common people. But the uprising foundered when details of the plan leaked.

While the others failed to garner much support,Wyatt raised an army of about 4,000 men in Kent. They marched on London where armed Londoners loyal to Mary turned out in the narrow streets of the Capital. They repelled Wyatt’s forces, and he was captured, tortured, and eventually put to death. The Duke of Suffolk, father of Lady Jane Grey, was also executed for his part in the plot, while Sir Peter Carew fled to France and Sir James Croft received a pardon. Suffolk’s involvement in the plot pushed Mary to order Jane Grey’s execution, something she had wished to avoid.

Mary believed Elizabeth was involved in the plot and ordered that she be taken to the Tower of London where Mary hoped she would confess under interrogation. Elizabeth may have seen Jane’s scaffold when she entered the Tower, a stark reminder of her own perilous position.

However, all efforts to uncover evidence that Elizabeth was party to the rebels’ plans failed. Even on the scaffold, Sir Thomas Wyatt, the captured leader, refused to implicate her. Yet Queen Mary was still not convinced that Elizabeth was innocent.

It must have come as a shock to Elizabeth when, after two months, Sir Henry Beddingfield, recently appointed Constable of the Tower of London, arrived with one hundred men. He told her that she was to leave the Tower; the date — the anniversary of her mother’s execution 18 years earlier — was probably deliberately chosen. Wary of her sister’s intentions and in fear of her life, Elizabeth was taken by river to Richmond Palace. She remained there for one night only, for Beddingfield had orders to take her under heavy guard to the Royal Manor at Woodstock in Oxfordshire, where she was to be kept under house arrest.

The journey took four days, passing through Windsor, via Eton, where the college boys ran out to cheer Elizabeth on her way. The large escort, with all the men dressed in a blue livery and the princess travelling in litter, took on the appearance of a royal procession, and word of Elizabeth’s release from the Tower had spread. All along the route, people rushed out to cheer Elizabethan her way, shouting good wishes and encouragement and throwing gifts of flowers, cakes and wafers (biscuits) into her litter.

Elizabeth spent a night at Sir William Dormer’s house at West Wycombe. On the next day she passed through Aston Rowant, where cheering people lined the road. Five men rushed to the church to ring the bells.

They were soon arrested for their excessive enthusiasm. In the 19th century, Agnes Strickland1 wrote

‘Great sympathy and affection were testified by the country people for the distressed heiress of the Crown, Elizabeth 1. They ran in crowds to gaze upon her and greeted her with loving words and prayers for her weal. But five men, as she passed through Aston, for ringing the bells were commanded to ward by order of Lord Williams, Sir William Dormer and Sir Henry Beddingfield.’

J B Neale2 also refers to five men ‘clapped in ward’, while Anne Somerset3 mentions four men, not five.

The enthusiastic reception Elizabeth received from the common people was a nightmare for Beddingfield who was charged to keep her under close watch. The cavalcade went on to Rycote, near Thame, where Sir John Williams hosted a lavish welcome in his brick-built home which was said to resemble Hampton Court Palace. To Beddingfield’s consternation, Williams showered Elizabeth with gifts of jewels and invited many local dignitaries.,including Robert King, Bishop of Oxford. While he was initially a supporter of Queen Mary, Williams showed his political skills by ‘hedging his bets’ and treating Elizabeth well. She did not forget his kindness, referring to him as ‘my favourite uncle’ .

Sir John Williams died in 1559, less than year after Elizabeth came to the throne. He lies in a magnificent tomb in the chancel of St Mary’s church in Thame, beside his wife Elizabeth.

Only a fragment of a stable survives from William’s house at Rycote, but the building which housed the school he founded in 1559, still stands. In his will he bequeathed a sum of money to create an establishment of learning for all comers. The school continues to this day but on different premises.

After spending a night at Rycote Elizabeth’s journey continued and she arrived at Woodstock on 23rd May 1554. She remained there until April 1555.

***

One person who almost certainly did not travel to Woodstock with Elizabeth was her faithful governess and confidante, Katherine Astley (Kat).

Portrait thought to be Katherine Astley , Lord Hastings Private collection, sourced via Wikimedia Commons

According to David Starkey4, Elizabeth was separated from most of her servants soon after she was brought to Whitehall in February 1554. Kat was probably amongst them, and likely did not accompany her mistress to the Tower. She may have been placed immediately into the custody of Sir Roger Cholmeley, because of her Protestant leanings. He kept Kat under what Starkey terms “protective custody” until her release and return to Elizabeth’s side in the autumn of 1555.

Had Kat travelled through Aston Rowant with Elizabeth, she would have been passing the former home of her grandfather, Sir John Champernowne, who died there in 1503. In the mid-14th century, Thomas Champernowne married Eleanor de Rohant, who brought extensive lands, lands including the manor of Aston Rowant, into the Champernowne family of Devon. In 1528, Katherine’s father, Sir Philip Champernowne conveyed the manor of Aston to his relative, Henry Courtenay, Earl of Devon and Marquess of Exeter. Courtenay sold the property soon after he acquired it.

Rosemary Griggs

6 April 2025

Notes

1 Strickland, Queens of England, Vol III

2 Neale, Queen Elizabeth

3 Somerset, Elizabeth

4 Starkey, Elizabeth, The Struggle for the Throne